“Our Memory has no guarantees at all, and yet we bow more often than is objectively justified to the compulsion to believe what it says.”

— Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

Introduction

In September 2023, I began a year-long research project intent on examining the impact that personal traumatic experiences (PTEs) have had on college writing classrooms. The subject was of great personal importance, given how PTEs have shaped my work, first as a student, and later as a professor. Several of the instructors that I encountered over the course of this investigation had adopted pedagogies that were largely informed by writing as healing (WAH) scholarship. These “leaned into” the traumatic experiences of students by attempting to create a space to process and overcome these experiences within the context of their writing assignments. However, as I reviewed the assignment prompts and delved deeper into the student responses, a troubling pattern began to emerge. While many students found the prompts cathartic, a subset of student responses raised concerns about the potential risks these assignments posed, specifically, the potential for these assignments prompts to generate false memories. By acquiring an understanding of how false memories are formed in clinical settings and analyzing the prompts produced by some of these instructors, this inquiry will bridge gaps between cognitive and behavioral therapy and WAH scholarship, identifying potential risks, and offering insights into how those risks may be reduced.

Literature Review

PTEs have had an undeniable impact on college students in recent years. In fact, several studies over the past decade have indicated an increase in the number of students whose education has been impacted by PTEs. According to researchers at the University of Minnesota, individual exposure to PTEs generally peaks between the ages of 16 and 20, with most students experiencing at least one significant trauma prior to the end of their college experience (Anders, Frazier, & Shallcross). PTE exposure rates in studies prior to the Covid-19 pandemic ranged from 52% (Owens & Chard) to as high as 85% of college students (Anders, Frazier, & Shallcross). Moreover, post-pandemic studies have found that as high as 99% of undergraduate students have reported at least one significant PTE that has impacted their academic performance (Tayles). Given the prevalence of PTEs among the college population, and the popularity of constructivist writing pedagogies which encourage students to construct knowledge by drawing source material from personal experiences, it is unsurprising to see how PTEs have increasingly impacted learning in college classrooms.

Today, student learning is most impacted by PTEs in the context of writing classrooms. After all, the therapeutic benefits of expressive writing have long been acknowledged by experts in the field of clinical psychology and have been adopted as a tool in a variety of cognitive and behavioral therapies for the past 50 years (Pennebaker & Beall). This is often cited as justification in WAH scholarship for well-meaning instructors to provide a space for students to explore personal experiences through writing assignments. While these efforts to support students are commendable, the lack of a clinical understanding of trauma can pose a very serious problem for some. As observed by Michelle Day, writing pedagogies that address trauma “rely almost exclusively on humanities-based perspectives on trauma (which center on representation and memory) and almost never draw from clinical perspectives” (3). Day explains that while it is laudable for WAH scholarship to acknowledge that “trauma impacts learning [. . .] and writing impacts healing, this literature does less for a sophisticated understanding of how trauma impacts learning/writing [and] what ethical practices best promote psychological safety” (17). In essence, writing pedagogies that embrace the healing potential for writing in college classrooms may inadvertently do more harm than good (Carello & Butler 155). It is therefore vital to bridge some of the disciplinary gaps that exist and explore WAH practices with a more critical eye to ensure the best student outcomes.

Understanding False Memories

False memories have been a subject of interest in the field of clinical psychology for most of the 20th century. According to the American Psychological Association, a false memory is “a distorted recollection of an event or [. . .] of an event that never actually happened. False memories are errors of commission, because details, facts, or events come to mind, often vividly, but the remembrances fail to correspond to prior events” (APA Dictionary of Psychology). False memories, often referred to as recovered or illusory memories, can vary in severity, and those who have experienced personal traumas are often predisposed to them. In minor cases, individuals may simply recall specific details that do not align with veritable fact. One example from my life occurred in during my freshman year of college, when I was struck by a drunk driver. When questioned by police at the scene, I described the vehicle that struck me as a white Ford Expedition. Luckily, a good Samaritan witnessed the accident, then followed the driver onto the interstate as they fled the scene. After calling 911, police executed a traffic stop, then arrested the driver on suspicion of DUI and charged them additionally with a hit-and-run. What shocked me in the weeks to follow was the fact that the SUV turned out to be a white Nissan Pathfinder, not a Ford Expedition, despite the fact that (even today) I can close my eyes, envision the front of the vehicle barreling toward me, and see clearly the Ford emblem displayed on its grill. This memory is vivid for me—but clearly that recollection was not supported by the evidence.

When minor cases of false memories occur, they can have massive consequences, particularly when concerning eyewitness testimony during criminal investigations. Consider then the extent of the damage that can occur in extreme cases, when memories of events that never occurred are implanted into a person’s memory. Research conducted by Dr. Elizabeth Loftus during the “memory wars” of the 1990s focused on the phenomenon of “repressed memories.” Throughout her investigations, Loftus demonstrated how fabricated memories were being implanted in patients by therapists, and were not, in fact, recovered memories that had been repressed due to trauma (Patihis et al.). During an interview on the podcast Speaking of Psychology, Loftus explains:

Some patients were going into therapy—maybe they had anxiety, maybe they had an eating disorder, maybe they were depressed, and they would end up with a therapist who said something like well, many people I’ve seen with your symptoms were sexually abused as a child. And they would begin these activities that would lead these patients to start to think that they remembered years of brutalization that they had allegedly banished into the unconscious until this therapy made them aware of it [. . .] My work showed that you could plant very rich, detailed false memories in the minds of people. It didn’t mean that repressed memories did not exist [. . .] but there really wasn’t any credible scientific evidence for this idea of massive repression, and yet so many families were destroyed by this unsupported claim. (Luna)

Although Loftus does not discount the possibility that repressed memories could exist, she does demonstrate that, under certain circumstances, memory can be manipulated, causing people to recall things that are either inaccurate or never happened.

Generating False Memories

Despite how complicated our cognitive processes are, creating false memories in the clinical settings proved remarkably simple. According to Loftus’s earlier research, false memories can be implanted through a blend of trust, misinformation, imagination exercises, and repetition (False Memories; Scoboria et al.). To better understand how this occurs, it may help to think of false memory creation as a four-step process:

- A person of authority (e.g., professor) gains the trust of a subject (e.g. student);

- That authority uses the power of suggestion (e.g., leading questions) and claims supported by anecdotal evidence to allude to the existence of a repressed memory;

- The authority prompts the subject to “remember” when something might have happened to them, encouraging them to add in their own details; and

- The authority encourages the subject to imagine how they might feel in certain circumstances, leading to something that Loftus terms “imagination inflation.”

To better observe this process in action, allow me to revisit one of my own false memories—the memory of the night that I was struck by that drunk driver. First, when the firefighters arrived on scene, I immediately recognized my friend’s stepfather. I had known him for approximately three years prior to seeing him on the scene that night, and following that event, a friendly face immediately had my trust. As an EMT checked my vitals, he did his best to keep me calm, then casually asked me about the vehicle. I described it initially as a white SUV. So far, so good. However, he then began asking leading questions about the kind of SUV that I thought it was. Initially, I did not remember, but then he asked me to close my eyes and think carefully. Did I see a logo? Maybe a round name plate—like Ford? Or did I see the head of an animal—Dodge, maybe? When I closed my eyes, I saw a pair of blazing headlights just before the collision, and a round logo on the grill between them—the Ford logo. He asked me to consider the size. Was it a smaller SUV, like an Explorer, or was it a larger SUV, like an Expedition? Given how large the vehicle seemed to me at the time, I thought it had to be the big one—the Expedition of course. Over the next ten minutes, as we the state troopers to arrive, my friend’s stepdad continued to ask me questions about what happened—repetitive questions that had those details circulating through my mind. Once the police arrived on scene, I had a very detailed description of the SUV—a description that I knew was accurate. That is until the state trooper picked up a piece of plastic on the ground nearby. That plastic was a piece of the fender of a late model Nissan Pathfinder, and it matched the white Nissan Pathfinder that they had pulled over 5 miles north on Interstate 90.

Understanding the Risks and Benefits

As alluded to earlier, there are several risks associated with false memories. According to the American Psychological Association, illusory memories can often be just as vivid as those derived from authentic experiences, with all the same repercussions (APA Dictionary of Psychology). This means that false memories of negative experiences can induce the same traumatic responses in individuals who previously did not exhibit those symptoms (Otgaar et al.). Likewise, as individuals with existing diagnoses of PTSD and depression are particularly susceptible to memory distortion, creating new false memories may have a compounding effect that complicates and endangers their road to potential recovery (Otgaar, et al.). Depending on the subject of these memories, they can often lead to social isolation, family rifts, and can have legal implications, particularly when included as testimony in criminal or civil cases.

Though there are many negative implications to consider, false memories do have some limited therapeutic benefits as well. One application of false memories that emerged from Loftus’s research came in the form of diet modification, particularly for individuals who are struggling with chronic health conditions brought on by obesity. In one case study, Loftus determined it was possible to implant false memories to make people more averse to fatty foods. According to Loftus, “[We] planted a false memory that you got sick eating strawberry ice cream. People told us they didn’t want to eat it as much” (False Memories, 2013). Similarly, Loftus explained that researchers have also successfully implanted positive memories about healthy foods, and as a result, helped individuals to make healthier dietary decisions. Today researchers are continuing to explore whether implanting false memories through hypnotherapy might help some patients to counter their physiological responses that are associated with negative experiences which impact patients with various forms of PTSD and anxiety disorders.

Research Questions

With a basic understanding of what false memories are, where they come from, and the positive and negative implications associated with them, the next step is to determine whether they indeed pose a risk to writing students. For this reason, this investigation will focus on the following research questions:

- Could writing assignments generate false memories for students?

- If so, what steps can instructors take to manage this risk in the future?

Methods

Participants

This inquiry focused primarily on how undergraduate students responded to writing assignments in two first-year composition courses. Preliminary findings were based on a sample of 92 undergraduate students enrolled at ten different institutions across various states. Among them, 23 students were sampled from two-year colleges in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, while 69 students were enrolled at public four-year universities in Georgia, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania.

Besides the students who participated in the surveys, two instructors volunteered artifacts for analysis as well. These instructors were referred to the researcher by students who participated in the survey and, following a brief conversation about the project, volunteered two prompts for evaluation—one for a memoir project, another for an autoethnography assignment. As such, both artifacts analyzed for this investigation were specifically referenced by students who participated in the initial investigation.

Data Collection

The first data collection tool employed during this investigation was a qualitative survey that was initially designed to examine the impact of trauma on the undergraduate writing student experience. This survey consisted of ten multiple-choice questions, intended to gain insights into how trauma might have impacted student learning. Additionally, two short-answer questions provided students an opportunity to explain how trauma presented during specific assignments and describe their response.

In addition to this survey, an artifact analysis of two assignment prompts was conducted. These prompts were volunteered by instructors, and both were actual assignments that sampled students referred to in their narrative responses. A rubric was devised based upon the prior research of Dr. Elizabeth Loftus. This rubric evaluated the writing prompts according to the four-step process (outlined previously) that led to the generation of false memories in Loftus’s previous studies. Reading the assignment prompts through that lens, each one was evaluated to determine whether there was evidence that instructors tried to establish trust with students, used of suggestive language to guide student responses, and incorporated imaginative exercises or repetition that might cause imagination inflation. Artifacts were then scored according to a three-point scale in each area of interest (See Table 1).

| High Risk 3 | Moderate Risk 2 | Low Risk 1 | |

| Step One: Evidence of Trust | Prompt makes significant effort to establish trust with students | Prompt makes some effort to establish trust with students | Unclear whether prompt attempts to establish trust with students |

| Step Two: Suggestive Language | Prompt makes significant use of suggestive language | Prompt makes some use of suggestive language | Prompt does not make significant use of suggestive language |

| Step Three: Students Elaborate Take Ownership Over Memories | Prompt requires students to explore and elaborate on potentially traumatic memories | Prompt offers students the option to explore and elaborate on potentially traumatic memories | Prompt does not require students to explore and elaborate on potentially traumatic memories |

| Step Four: Imagination Inflation | Prompt requires students to use imagination to fill gaps in memories | Prompt offers students the option to use imagination to fill in gaps in memories | Prompt does not permit students to use their imagination to fill in gaps in memories |

Table 1: Rubric used to assess false memory risk for assignment prompts.

Two assignment prompts were examined as a part of the artifact analysis: one from a memoir essay assignment, sampled by a first-year writing course at a community college in western Pennsylvania, and another from an auto-ethnographic essay assignment in a first-year writing course at a four-year university in Minnesota.

Preliminary Findings & Discussion

Student Survey Responses

As I mentioned previously, the initial goal of this research was not intending to address the topic of false memories explicitly. Instead, these surveys were intended to determine the impact that personal traumatic experiences have had on post-secondary writing pedagogies. This initial student survey returned 92 student responses (23 from two-year colleges and 69 from four-year universities). Of those responses, 72 had described course assignments that required students to engage with the subject of personal traumatic experiences, with an additional 15 students indicating that writing about personal traumatic experiences was an option in at least one of their writing courses.

The suggestion that false memories may have impacted the student experience first emerged in response to the short answer portion of the survey, specifically in response to the following prompt: Describe your experience with an assignment that may have been impacted (directly or indirectly) by personal trauma. Initially, students described a variety of personal narrative assignments that asked them to explore moments of personal growth or change—assignments which seemed rather innocent on the surface. However, as I read about a personal memoir assignment, one student mentioned “recovered memories.” According to this response, “I didn’t remember a lot about what happened. But when I write about it, I start [to] remember. It was weird. Like new memories came up that I didn’t even know were there.” At first, this comment seemed to be an outlier, but as the survey accrued more responses, the following comments stood out as well:

- “Writing about the attack made me start to doubt what really happened. Its like I couldn’t tell if it was real. I thought I knew the truth but now I’m not sure.”

- “I felt like I had to come up with a good story for the assignment. I think I might have exaggerated some parts just to make it more interesting.”

- “I wrote about something really personal for my assignment, but when I read it after class was over, it didn’t feel like my story anymore.”

- “[Dad] called me a liar when he read it over for me. Now we don’t talk and I don’t know what to do.”

It is worth noting that these students were a definite minority and all were enrolled in different classes and institutions. Still, four of the 92 participants mentioned specifically changing memories and subsequent confusion in response to writing assignments that evoked trauma, and three mentioned a degree of social isolation (with friends or family members) as a result. Although it is difficult to say whether these students were generating false memories, the word choices of these students seemed to imply that something may have been going on with their memories while completing their assignments. Add in the comment about someone no longer talking to their father because of an assignment, and it seemed that (in the very least), a supplemental investigation may be warranted.

Artifact Analysis

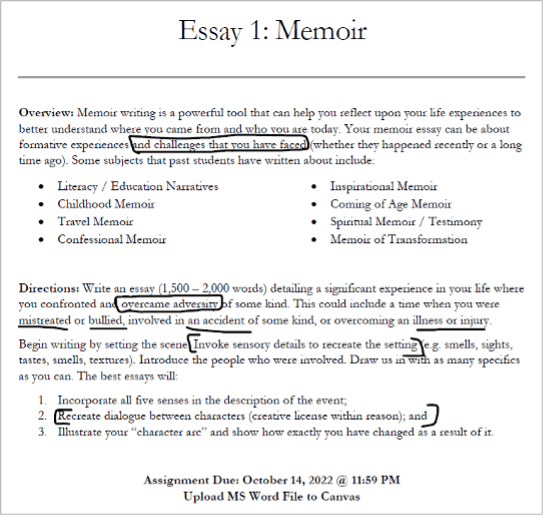

One assignment discussed by the students in the survey was a memoir essay assigned to a first-year composition course at a community college in western Pennsylvania (See Figure 1). This assignment required students to produce a 1,500-2,000 word essay exploring a significant experience in the student’s life when they “overcame adversity.” While adversity itself is not necessarily synonymous with trauma, students often encounter adversity through traumatic experiences, with some researchers using these terms “interchangeably to refer to ongoing overwhelming stressors that erode our health and well-being” (Jennings 9). Although not all adversity qualifies as trauma, adversity which activates a traumatic response like hyperarousal (fight or flight) or hypoarousal (freezing) would constitute a trauma. While the prompt in question does not require students to explore a past trauma, this assignment leaves the option open for students to revisit a potentially traumatic memory if they choose. The language used in the assignment prompt also appears to be moderately suggestive, assuming that students have overcome adversity, and then providing leading language to guide students toward the subjects of bullying, accidents, illnesses and injuries. However, the element in the prompt that is perhaps the riskiest is the mention of “creative license.” In this case, as the instructor directly encourages students to incorporate descriptive writing that appeals to all five senses and re-create dialogue “within reason,” which could risk manipulating memories through imagination inflation. Overall, the memoir assignment prompt scored 8 out of a potential 12 points, which indicates that this assignment, as designed, carries a moderate risk for generating false memories in students.

Figure 1: Memoir essay writing prompt form a two-year college in Pennsylvania

The second assignment that was raised in the student survey was an autoethnography essay assigned by a professor at a mid-sized, four-year university in Minnesota. Unlike the memoir assignment above which provided students with an option to explore experiences that might be traumatic, the autoethnography assignment required students to write explicitly about the COVID-19 pandemic, arguably one of the most significant collective traumas of the current generation (see Figure 2). This assignment prompt also had suggestive language, making an assumption that the social lives of students had been significantly changed, and it attempted to support this assumption with an example from the instructor’s own life (bolstering the instructor’s ethos). Not only this, but the example from the instructor’s life (their new involvement with an Xbox gaming community) could be seen an attempt to garner trust with some of their students. Suggestive language continues throughout the overview of the assignment, as the instructor suggests some ways that student lives might have been changed, with signal words like “perhaps” and “maybe” to guide students subtly toward potential topics. However, it is also worth noting that this assignment does not explicitly encourage the use of “creative license” or other phrases, which would lead me to believe that imagination inflation might not be a significant concern. Overall, this assignment prompt scored an 8 out of 12 as well, indicating that this too may also carry with it a moderate risk for creating false memories.

Figure 2: Autoethnography essay prompt from a four-year university in Minnesota.

Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into the potential of writing prompts to evoke false memories in writing students, there are several limitations to consider. First, the size and scope of this study were limited. With only 92 student survey respondents, this is hardly a representative sample of writing classrooms, and as such, these findings are not generalizable. In short, this investigation simply observed a potential risk that merits further examination.

A second potential limitation can be observed through the artifact analysis itself. The rubric used to interrogate the writing prompts was adapted from research that was conducted by Loftus in a clinical setting. While this provided a structured framework by which to evaluate the writing prompts that were volunteered by instructors, the complexities of classroom dynamics and those in clinical settings differ significantly. For example, therapeutic interventions present in clinical settings are typically absent in the classroom setting. When a student discloses a previous trauma through a writing assignment, the inciting incident or memory itself will typically not be deconstructed in the same way that a clinician would engage with the subject if it were raised during a session of cognitive or behavioral therapy. Because of this, I would caution that the rubric employed in this study serves as a starting point. Future research is necessary to continue to tailor this rubric to address the classroom context more specifically.

Finally, as mentioned previously, this article emerged from the findings of a tangentially related research project examining the effects of PTEs on writing pedagogies. As such, implementing additional qualitative measures could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how writing assignments may trigger false memories. Naturalistic observations of instructors introducing writing assignments to students, in-depth interviews with both instructors and students, and focus groups could prove useful to acquiring a more practical understanding of this subject.

Conclusions

It is important to note that differentiating between false memories and memories rooted in authentic experience is very difficult. For that reason, this study does not have sufficient data to determine whether the “recovered memories” disclosed by the students in their surveys were authentic memories or not. Additionally, this study does not offer a causal link between the sampled writing prompts and the memories generated by the sampled students. However, I would suggest that comments offered by students indicating that these memories were “confusing,” caused tension with family members, and that some students may have exaggerated claims while completing those assignments indicate we cannot rule illusory memories out as a possibility either. After a close reading of two assignment prompts, it became clear that some of the strategies used by psychologists to implant false memories during clinical research were also observable within the context of some writing assignments. This demonstrates that there could be a moderate risk in students developing false memories, at least within the context of the sampled projects. This risk could be reduced by analyzing the design of those assignments and taking a few key precautions.

- Do not require students to engage with PTEs in the context of a writing assignment.

Writing is highly therapeutic. It reduces the symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), enhances emotional processing, reduces anxiety and depression, and promotes social support. For those reasons, a subset of the student population will continue to explore their personal traumas in the context of almost any writing assignment. However, for writing to have these therapeutic benefits, the individual must be prepared for the experience. If a trauma is too recent or too severe, it is simply not recommended to have students explore those traumas within the context of a course assignment. For that reason, it is recommended that instructors not design assignments that force students to explore the topic of trauma. As traumatic experiences place individuals at higher risks of being impacted by false memories, it is vital to provide students with alternative options to ensure that no additional harm is done.

- Have resources ready for those occasions when students choose to write about their PTEs.

On those occasions when student do engage with personal traumatic experiences (either directly or indirectly), it is essential that instructors be prepared. Many colleges and universities require instructors to list mental health resources that are available on campus within their course syllabi. This is a good first step. However, with how overburdened counseling centers on campus have become, and as funding for mental health on college campuses continually falls short of student need, simply including campus resources is not enough. For this reason, instructors should compile a list of regional resources as well. Provide direct numbers for regional crisis centers, as well as reputable national helplines.

- Avoid suggestive language when designing assignment prompts.

Individual trauma responses differ from one person to the next. Although some experiences may be viewed as universally traumatic (e.g. witnessing a death, imprisonment, etc.), not all individuals will respond in the same way to that trauma. This means that while the COVID-19 lockdown of 2020 impacted most people across the United States in some way, the trauma inflicted was not universal. It is vital to not make assumptions about what does and does not constitute a traumatic experience. Going further, when a student is engaging with an experience that is potentially traumatic to them, it is essential to avoid using suggestive language that may influence how they process that experience. For example, there is a subset of the population which may not have been significantly hindered by the lockdown experience. Using suggestive language that labels the experience as “traumatic” poisons the well for those individuals, which may actually result in a false memory that inflicts some level of trauma on students who may not have described the experience as traumatic.

- Minimize the use of creative license to reduce the risk of “imagination inflation.”

Imagination inflation is one of the ways that an individual internalizes and assumes ownership of a false memory. It is the repetition of imaginative exercises which allows a thought to be developed and internalized, which then creates a new subjective “truth” for that individual. The writing process, by nature, is incredibly repetitive. Consider how prewriting exercises allows you to begin with an idea, and how that idea evolves as it is guided through several drafts. Although creative license is appropriate for some writing genres (e.g. fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction, etc.), academic assignments where students engage with trauma should limit a student’s use of creative license to avoid establishing an environment that could risk students fostering false memories. This is not to say that we should eliminate creative license completely from writing courses. However, instructors should consider the rhetorical purpose and goals of their assignment, and then select the level of creative license that is appropriate to help mitigate these risks.

To better understand how false memories might be generated within the context of the writing classroom and the risks that this may pose to student health, additional research is necessary. Sample data that was explored in the context of this preliminary investigation is from a relatively small sample, and the variety of writing assignments employed in writing classrooms vary from one institution to the next. However, by taking steps to better understand how false memories are created, instructors will be able to continue to develop trauma informed pedagogies that will support their students and create healthier, more productive classroom environments.

Works Cited

Alexander, Khadijah S., et al. “Investigating Individual Pre-Trauma Susceptibility to a PTSD-like Phenotype in Animals. Frontier in Systems Neuroscience, 14 January 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2019.00085. Accessed 12 January 2024.

Anders, Samantha L., Patricia A. Frazier, & Sandra L. Shallcross. “Prevalence and Effects of Life Event Exposure Among Undergraduate and Community College Students.” Journal of Counseling Psychology, vol. 59, no. 3, 2010, pp. 449-457.

APA Dictionary of Psychology. The American Psychological Association. 19 April 2018. https://dictionary.apa.org/trauma. Accessed 12 February 2024.

Carello, Janice & Lisa D. Butler. “Potentially Perilous Pedagogies: Teaching Trauma is Not the Same as Trauma-Informed Teaching.” Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, vol.15, no. 2, 2014, pp. 153-168.

Day, Michelle. Wounds and Writing: Building Trauma-Informed Approaches to Writing Pedagogy. 2019. University of Louisville, Ph.D. dissertation.

False Memories : Skepticism, Susceptibility, and the Impact on Psychotherapy / Short Cuts TV Ltd. Films Media Group, 2013. https://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=240117&xtid=53552. Accessed 10 January 2024.

Great Courses, The. Understanding Trauma. The Great Courses, 2020.

Jennings, Patricia. The Trauma Sensitive Classroom: Building Resilience with Compassionate Teaching. Norton, 2019.

Luna, Kaitlin, host. “How Memory Can Be Manipulated.” Speaking of Psychology, episode 91, American Psychological Association, October 2019. https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/memory-manipulated. Accessed 23 March 2024.

Otgaar, Henry, et al. “What Drives False Memories in Psychopathology? A Case for Associative Activation.” Clinical Psychological Science, vol. 5, no. 6, 2017, pp. 1048–69, https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617724424. Accessed 12 April 2024.

Owens, Gina P.& Kathleen M. Chard. “PTSD Severity and Cognitive Reactions to Trauma Among a College Sample: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma, vol. 13, 2006, pp. 23-36.

Patihis, Lawrence, et al. “Are the ‘Memory Wars’ Over? A Scientist-Practitioner Gap in Beliefs About Repressed Memory.” Psychological Science, vol. 25, no. 2, 2014, pp. 519–30, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613510718. Accessed 4 March 2024.

Pennebaker, James W., & Sandra Klihr Beall. “Confronting a Traumatic Event: Toward an Understanding of Inhibition and Disease.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, vol. 95, no. 3, pp. 274-281.

Scoboria, Alan, et al. “A Mega-Analysis of Memory Reports from Eight Peer-Reviewed False Memory Implantation Studies.” Memory (Hove), vol. 25, no. 2, 2017, pp. 146–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2016.1260747.

Shaw, Julia. “Do False Memories Look Real? Evidence That People Struggle to Identify Rich False Memories of Committing Crime and Other Emotional Events.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 11, 2020, pp. 650–650, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00650. Accessed 20 April 2024.

Tayles, Michelle. “Trauma-Informed Writing Pedagogy: Ways to Support Student Writers Affected by Trauma and Traumatic Stress. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 38, no. 3, March 2021, pp. 295-313.

Learn more about the author on our 2025 Contributors page.