As any English Language Arts (ELA) teacher could tell you, teaching our subject is challenging. ELA teachers are called on to equip their students with the diverse literacy skills needed to succeed in a rapidly changing world. For ELA teachers this often means weaving together the teaching of literature, non-fiction reading, poetry, plays, memoirs, diverse forms of composition, listening and speaking skills, digital literacy, and critical literacies – just to name a few. Research indicates that most ELA teachers do all of this without referencing any curriculum for a majority of their instructional time (Kaufman et al.). Paradoxically, though, ELA is also the subject of intensive scrutiny into teaching and learning. In the last five years, since the Covid-19 pandemic transformed learning, media reports have centered on concerns about standardized test results (e.g., Goldstein), students’ reading skills (e.g., Sold a Story), and the literacies that students have (or don’t have) when they enter higher education (Horowitch).

As states reevaluate and, in many cases, replace the Common Core State Standards with new state-created academic standards, the work of teaching ELA seems poised for further change. In Minnesota, adoption of new ELA standards has taken place amid additional public and governmental debate about literacy education; recent years have seen increased media discussion how we should teach reading, what texts should be read in schools, and what the purpose of education should be. And, amid all of this, ELA teachers are frequently left to make their own decisions and curriculum for their classrooms.

These forces inspired the study I share in this paper. In spring 2023, I launched my dissertation study: an examination of how middle school ELA teachers in a single Minnesota middle school made decisions about what to teach, exploring how teachers understood and enacted ELA daily in their classrooms. This study was directly informed by my work as a secondary ELA teacher, a reading- and literacy-focused K-12 instructional coach, a supporting school leader, and by my work as a Ph.D. student, research assistant, and consultant focused on middle grades and adolescent reading and literacy. Through my study, I sought to gain insights into how teachers thought about and taught reading and literacy in their own middle school ELA classrooms.

In this paper, I present a subset of my dissertation study’s findings (Taylor). Specifically, I focus in on what made my study unique to Minnesota, such as the 2020 Minnesota Academic Standards for English Language Arts (Minnesota Department of Education, 2020 Minnesota K-12 ELA Standards). In my study, the new Minnesota ELA standards played an unexpectedly large role in shaping teachers’ instruction in classrooms. I provide insights into how my participants thought about teaching ELA in light of these standards, and the ways in which teachers’ and administrators’ understandings about the still new academic standards impacted student learning.

Study Overview and Context

The research I present in this piece is drawn from a larger study, in which I spent several exploring ELA teaching and learning in two middle school ELA classrooms. In this piece, however, I will focus on my study’s insights into teacher beliefs about and enactments of ELA in Minnesota classrooms. The research question I will focus on in this paper then, is as follows:

RQ: How do teachers’ beliefs about their roles interact with contextual factors such as standards and school expectations to shape ELA instruction in their classrooms?

As a qualitative and exploratory study, my research focus, questions, and theoretical framing shifted over the course of my study. Notably, my hunches about what I anticipated seeing in classrooms were quickly disproven by the data I was collecting; as a result, I continually adjusted my focus and revised my tools to make sure that my research adequately captured the complexities of teaching middle school ELA every day.

Literature Reviewed

My study was informed by my wide reading in several different domains of educational research. The first area that was informative for my study was broad reading in disciplinary literacy, which researchers have defined as the literary practices adopted and privileged by experts in specific fields (Moje; Shanahan and Shanahan). Disciplinary literacy is premised on the understanding that different disciplinary communities read and make meaning of the world in distinct ways; for example, historians read with an eye toward sourcing questions such as who wrote a text, when, and in what context (Shanahan and Shanahan; Wineburg). These practices are distinct from the literacy practices of their colleagues in other fields; for example, mathematicians read with an eye toward precision of expression and proof (Fang and Chapman). Disciplinary literacy has, in recent years, come into conversations about secondary teaching and learning; the Common Core State Standards for ELA, for example, also contained differentiated literacy standards for social studies, science, math, and other subject areas that teachers were expected to incorporate into their instruction in “discipline-specific” content (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers 64).

In ELA, researchers have identified disciplinary literacy practices unique to literary scholars, drawing on expert studies of English professors (Rainey, What Does It Mean; Rainey, “Disciplinary Literacy”; Reynolds and Rush). Complicating matters, though, is the reality that ELA as it exists in secondary schools is a multidisciplinary subject (Rainey et al.); teachers of ELA are typically expected to teach not just literary reading and analysis, but also theatre, poetry analysis, creative writing, other writing skills, speaking and listening, and any number of other skills (Smagorinsky). As a result, it has been challenging to infer a straightforward application between what we know about disciplinary literacy among literary scholars and the teaching and learning practices of K-12 ELA teachers.

A second body of literature that informed my study was research focusing on teacher decision-making in literacy contexts. Much of the existing literature (e.g., Ruppar et al.; Siuty et al.; Troyer; Smagorinsky et al.) focuses on how educators make decisions about enacting curriculum that already exists. My reading of the literature suggests that much less is known about how literacy teachers make decisions about what to teach in the absence of curriculum, as was the case for participants in my study.

Finally, I looked broadly at the existing research and theoretical writing about English Language Arts as a subject area in America’s secondary schools. The relationship between college English and ELA as it exists in secondary schools has been problematized for decades (Luke; Williams). In his 2004 piece, Luke called for a “broad and thoroughgoing rethinking of the very intellectual field that we are supposed to profess” (86), based in his insight that ELA in K-12 schools can be seen as “forever caught in some kind of perverse evolutionary time-lag, parasitic of university literary studies” (85). Decades later, though, clarity about the purposes and aims of English education seems unresolved, and guidance and answers seem to have increasingly come from academic standards including the Common Core State Standards as well as the content of state, national, and international assessments.

My review of the available literature did not find studies looking at the core questions central to my study, and only a handful of non-interventionist studies looking at how educators thought about and enacted their beliefs about the purposes of English Language Arts teaching. Much of the available research on ELA teaching focuses on how higher education thinks of the subject. Instead of continuing this trend, my study sought to center the perspectives and insights of in-service teachers; this is in direct response to calls from researchers (e.g., Hinchman and O’Brien) for research that embodies hybridity in disciplinary literacy – that looks at the ways in which higher education and K-12 conceptions of disciplinary literacy do and do not relate to one another.

Methods of Inquiry

I designed a qualitative research study that privileged depth over breadth in learning about teacher decision making in English Language Arts classrooms. Qualitative case study methods (Stake; Merriam) were utilized throughout the study design and implementation; these methods focus researchers on an individual case or multiple cases, which they seek to understand in deep and contextualized ways. For this study, I used a multi-case design. Each educator was viewed as an individual case. During data analysis, I fully analyzed one participant’s data first, then analyzed the other educator’s data before drawing comparisons (Yin).

On the advice of my dissertation committee, I focused my study on a single school site; this enabled me to assume that many contextual factors, such as school community, administration, professional development, and requirements were similar for participating educators. Focusing on a single site allowed me to pay attention to the individual factors that made each teacher and their instructional decisions unique.

Study Context

Given the nested design of this study—a study that examined individual educators’ practice and classroom teaching within a single school site—participant recruitment and site selection happened concurrently. I worked with colleagues at the University of Minnesota to identify sites where my former students, members of the Initial Licensure Program in English Education at the University of Minnesota, were now teaching, and then looked for overlaps, other connections, and possible “ins” with other members of their departments. It was during this process that I initially identified Westview Middle School (WMS) as a potential site for my study; I realized that I knew two members of the school’s four-person English Language Arts department. I use pseudonyms throughout this paper, in accordance with Institutional Review Board approval for the study.

Study Site

My study was located at Westview Middle School (WMS). WMS is the only middle school in the Westview Township School District, a small school district that serves about 2,000 students in a suburban community in Minnesota. In 2022-2023, when this study was conducted, WMS served approximately 500 learners. Approximately 60% of WMS’ students were white, 10% Black or African-American, 10% Hispanic or Latinx. 10% multiracial, 5% Asian Pacific Islander, and diverse other racial identities comprised the balance of the student population. Approximately one in three students qualified for Free or Reduced-Price lunch during this study, used as a stand-in measure for poverty. Around 5% of the students at WMS received English Learner services in 2022-2023.

As the only middle school in its district—and given the small size of its ELA department—WMS was an ideal site for my study. My study design was built around gaining in-depth data about the ELA teaching of focal educators; having two educators willing to work with me at Westview meant that, for approximately three months, I spent hours in the building multiple times a week. Students were friendly but, especially after my first observation or two, largely unbothered by my presence in the focal classes. I observed classroom instruction from mid-March through early June in the 2022-2023 school year, which set me up to observe end of year, culminating projects, a final unit of instruction and, in some cases, standardized testing and other mandated end of year assessments.

Because the district was so small, working with Natasha and Erin meant that I was spending time in the district’s lone 7th and 8th grade ELA teachers’ classrooms. Erin and Natasha had different personal backgrounds, teacher training, and teaching experiences. However, both experienced the same professional learning, collaborated in the same Professional Learning Community, and their classrooms were side by side, separated by only one wall.

Participants

Study participants were contacted and interest in participating was gauged before formally securing IRB and institutional permissions to conduct this study. As previously noted, both participants were known to me before the start of the study; this was important for the study as it enabled me to build trust with participants and to secure the needed institutional permissions. Ultimately, participants were consented through the Institutional Review Board process at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities.

Erin

Erin was a first-year teacher who taught 8th grade English Language Arts at Westview. She identified as a white woman. Erin had completed her Initial Licensure Program (ILP) and earned her M. Ed. at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities the school year before this study was conducted. While at the U, Erin took a course that I taught, which focused on equipping future ELA teachers with the knowledge and methods needed to support their students’ reading development. Erin and I built a relationship easily during this class, and stayed in touch as she completed student teaching, earned her Master’s degree, and ultimately started teaching at Westview. Before pursuing teacher certification, Erin had earned a Bachelor’s degree in English at a small liberal arts college and had worked with education and public health oriented non-profits through undergrad internships and post-graduation volunteering.

Natasha

As previously mentioned, after I realized that Erin was teaching at WMS, I came to learn that I had another connection on her teaching team: Natasha. Natasha and I had met through a previous research project, when I worked with ELA teachers and reading specialists in a different Minnesota school district. Natasha was in her 16th year teaching when she participated in this study, and she identified as a white female. When I launched my study, Natasha had been teaching 7th grade ELA at Westview Middle School for about a year. Natasha and I quickly realized that, although we didn’t knowingly interact, we were connected; she and I had both come into teaching through Teach For America, an alternative licensure pathway that, when we both joined in the early 2000s, was bringing thousands of non-traditionally certified teachers into some of the nation’s highest-need schools and districts. Natasha joined TFA after earning a Bachelor’s degree in English at a small liberal arts college, and continued her education while in the classroom, earning certification in multiple states and, eventually, a Master’s degree and Minnesota Tier 3 licensure. As Natasha noted in our initial interview, “I learned [teaching] while doing and then going to night classes for the first nine years of my career.”

Notably, then, Erin and Natasha had a few key similarities: their racial and gender identities, their undergraduate English majors, and their relatively recent arrival at Westview Middle School. Differences between the two that I thought might impact their instructional decision making included their years of experience (Erin: 1st, Natasha: 16th) and their teacher training pathways (Erin: traditional post-baccalaureate, Natasha: non-traditional). Finally, as Natasha noted herself, the schools where she’d taught for the past 15 years were mostly under resourced urban schools, which posed a contrast to suburban Westview Middle School and, Natasha suggested, impacted her beliefs about her work as an English Language Arts teacher.

Positionality

Because my relationships with participants were important in launching this study, it is important to briefly introduce myself, my positionality, and my background. I am a white, cisgender female who is originally from South Dakota. I graduated from a small liberal arts college with a Bachelor’s in Philosophy, joined Teach For America, and launched what has become my nearly two decade career in education. I spent thirteen years working with students and teachers in St. Louis, Missouri, where I worked in under resourced schools, most of which served predominantly Black learners. In the seven years I spent as an instructional coach in St. Louis, I worked mostly with beginning educators, a majority of whom identified as white women. Notably, I have characteristics in common with both participants: our racial and gender identities, our liberal arts undergraduate degrees, our advanced degrees in education, and our teaching experiences provided common ground.

As noted earlier, I had preexisting relationships with both participants in this study. I believe that, rather than hindering or harming my interpretations, these relationships instead gave me easier access to data, provided us with a foundation for more natural and unfiltered conversations about teaching, and helped my ongoing presence in participants’ classrooms feel less conspicuous. That being said, my interpretation is based in my perceptions, and my preexisting relationships with participants may, in fact, have altered how teachers taught or the ideas they shared with me during our interviews; I sought to address these potential impacts by collecting diverse data, by triangulating among multiple data sources in my analysis, and by privileging depth of our connections. Showing up consistently in classrooms for months, leaving time for informal, personal check ins, and making my presence as unobtrusive as possible were always that I sought to minimize the impacts of my relationships with participants.

Data Analysis

As a qualitative study, I focused my data collection and analysis on two categories of data: 1.) teacher self-reported data and 2.) classroom observation data. Self-reported data was analyzed through transcripts of two 45-60 minute long interviews with participants – one conducted at the start of the study and the second after observations had concluded. Classroom observation data was also largely textual, as I took detailed observation notes in participants’ classrooms over a span of about 3 months, observing instruction in a focal class one or two times a week (n:10-12 observations per class). These broad categories of data were supplemented by artifacts (e.g., worksheets, instructional plans) I took pictures of during observations. Additionally, I occasionally used voice memos as I was driving away from the school to remember key moments or asides with the teacher as I left the room that weren’t captured in my typed notes.

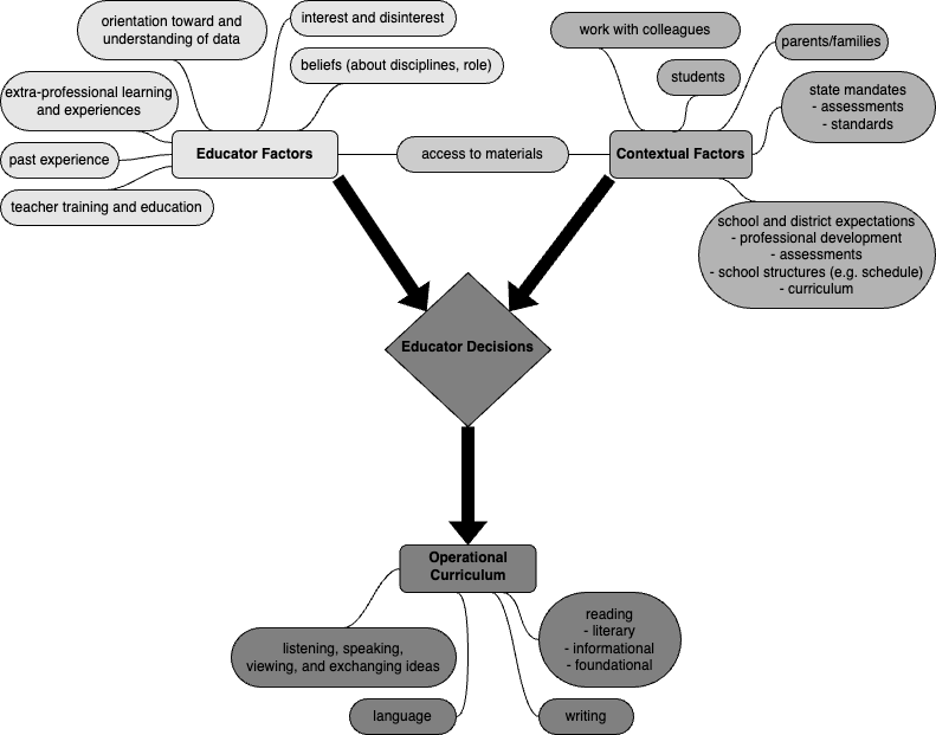

These data were analyzed through multiple rounds of qualitative coding (Patton; Saldaña). In the first round, I applied provisional codes (Saldaña) based in a theoretical framework I built during my review of the literature, largely concentrated on explaining teacher factors and contextual factors that impacted instruction, as well as seeking to find trends in observation data (e.g. the strands teachers were privileging and the types of texts students were both analyzing and creating). During first round coding, I revised my conceptual framework significantly. During second round coding, I consolidated codes, sought patterns, and checked my framework against the data; my revised conceptual model incorporated factors that I had underestimated in my initial framing of the study, including state standards and availability of instructional materials. The patterns and trends that emerged led me to develop an overall conceptual model for teacher decision-making (see fig. 1), as well as the findings discussed at greater length in my dissertation (Taylor).

Fig. 1. Final Conceptual Framework for ELA Teachers’ Decision-Making from Taylor, Disciplinary Literacy.

Findings Specific to Teaching ELA in Minnesota

As noted, this was a much larger study, with wide-ranging findings and implications for educators and teacher educators alike. Of particular interest, though, are my study’s implications for ELA educators in Minnesota. My study, conducted in the 2022-2023 school year, took place amid significant winds of change in reading, literacy, and ELA instruction in Minnesota. Minnesota was in the process of adopting the 2020 ELA standards (Minnesota Department of Education, 2020 Minnesota English Language Arts (ELA) Standards Implementation Timeline); although these new standards weren’t yet fully adopted, they were available online and many educators, including participants in this study, were already using them to shape ELA instruction. Additionally, the Minnesota Reading to Ensure Academic Development Act, better known as the READ Act, was debated and passed by the Minnesota State Legislature while interviews and classroom observations for my study were underway; the READ Act was signed into law just weeks before the end of my observations, in May 2023 (Legislation). Amid these significant changes, I spent approximately three months embedded in and observing teaching and learning in one of each educator’s classes; I observed multiple times a week, taking extensive notes and seeking to understand how teachers understood the work of teaching ELA. These notes were complimented by – and at times in tension with – teachers’ self-reported values, priorities, and goals, which I mostly learned about through our pre- and post- interviews.

Broader findings less specific to Minnesota are reported in other publications (Taylor). For purposes of this paper, I focus on three findings with specific implications for ELA teaching and learning in Minnesota.

Finding 1: Teacher Autonomy, Constrained by Context, Shapes Instruction

As mentioned earlier, Natasha and Erin were largely left to their own devices to create and enact curriculum. This is unsurprising: a majority of ELA teachers nationally do not reference curriculum for a majority of their instructional time (Kaufman et al.). As reported elsewhere, this can lead to disjoined or incoherent instruction (Pauketat et al.). Unsurprisingly, then, Erin and Natasha’s ELA instruction looked, sounded, and felt very different. I briefly describe each educator’s teaching to illustrate these differences.

Instruction in Erin’s 8th Grade ELA Classroom

In first year teacher Erin’s classroom, students spent most of the duration of my study engaged in study of Maus (Spiegelman), a graphic novel memoir of the author’s family and their experiences in the Holocaust. Erin selected Maus as the focal text for their fourth unit of the school year – and their first whole-class book-length text – based on several factors. First, Maus dovetailed nicely with topics students were learning in their 8th grade Social Studies class, titled “Global Studies.” Second, Erin believed there were copies of the book available in the school (she later discovered there weren’t copies of the book, but was able to secure funding for a class set).

During their study of Maus, daily instruction in Erin’s classroom followed a typical cadence. Students would pick up a book and a daily work packet as they entered the classroom, typically engaging in a brief lesson or whole-class activity, then spending the balance of class reading a section of Maus and answering aligned questions in their packet. When I asked her how she came up with the questions she asked her students in these literary analysis activities, Erin replied:

When I was coming up with these packets… I was like, I want to write questions that I would want to answer as a 26-year-old person who reads. You know? And I would go online and look at these example units from Maus. And I’d be like, that question is so easy. Or like, that is not interesting. And there were so many of them that were purely just content based. And I was like, why would I waste their time only asking them about content when that’s not what I care about at the end of the day? I do care that you understand what the content was because it helps you do the other things. But I care about the other things! I care that you have transferable skills from this text to other texts. I’m not doing you a service by saying, “You know Maus like the back of your hand,” you know?… So I, yeah, I truly was just like—what am I curious about? What do I want to hear their thoughts on?

This is an example of typical instruction in Erin’s classroom during my study, but many days were atypical. At the start of my study, Erin’s students were analyzing and critiquing advertisements. Later in my study, students focused most of their attention on learning about other instances of injustice against groups on the basis of identity and creating an argument and presentation to content that the event they researched should be part of the 8th grade social studies curriculum at Westview.

It bears mentioning that Maus was the first book-length class that Erin read with her students during the 2022-2023 school year; as a former English major who talked at length during our interviews about her love for literature, Erin’s choice to de-center whole-class literary study of longer texts seemed to be in tension with the value she sees in literary study, the traditional heart of ELA teaching and learning in US secondary classrooms. I’ll return to this point after briefly describing instruction next door, in Natasha’s 7th grade ELA classroom.

Instruction in Natasha’s 7th Grade ELA Classroom

Veteran teacher Natasha’s classroom, in many ways, looked similar to Erin’s; separated by a single wall, the rooms had similar layouts, including built-in shelves packed with bins of middle grades and young adult literature, desks often configured into pods to support the day’s learning goals, and alternative seating options around the periphery. These similarities, however, didn’t consistently play out in how Natasha thought about and enacted curriculum in her 7th grade ELA classes.

In her 16th school year working with middle school ELA, Natasha’s interviews revealed that she was still actively working to create and enact a vision for ELA instruction. Rather than being set in a vision of ELA aligned to the literary analysis she studied in college, Natasha was actively making and remaking her vision for teaching in the subject and pushing back on the central role typically given to literature. In our final interview, Natasha explained:

Where… people, including myself, want more improvement for our students is not all in the analysis of literature. It’s in the production and communication of your ideas and the analysis of other people’s ideas… Everybody wants my students to write better, and spell better and—not be tricked by fake news and to cite their sources and to want the truth. And—that’s where I think we should be heading. That’s where most people want to be heading.

ELA instruction in Natasha’s classroom aligned to this instructional vision. Students were reading historical fiction novels independently during my observations, but the majority of instructional time and energy was focused on a rhetoric and debate unit. Students analyzed ethos, pathos, and logos, drawing on resources Natasha curated from Teachers Pay Teachers and colleagues. They applied these insights to their end of year project: end of year team debates, judged by classmates, where students created presentations and presented research-backed arguments in the style of the podcast “Smash, Boom, Best!” (Bloom). Literary study was present in Natasha’s classroom, but other literacies were consistently privileged during the three months I visited her class.

One factor that shaped decision-making in Natasha’s classroom were her own interests and disinterests. With no curriculum and dozens of standards to choose among, Natasha noted that the amount of choice was “a bit unnerving” and shared how it led her to make decisions about what to teach based on more subjective factors:

And so sometimes [colleagues and administrators are] like, what do you want to do in seventh grade? I’m like, I don’t want to read personal narratives so can we not do narratives in seventh grade? Which is not how you should vertically align… I don’t really want to read six pages of a fiction text because fiction just goes on and on forever– [that] doesn’t mean that we just shouldn’t do that in seventh grade.

Much like in Erin’s classroom, this quotation indicates how teacher interest directly shaped teaching in Natasha’s classroom.

Finally, Natasha’s beliefs about the work of teaching ELA were also shaped by her past teaching and instructional coaching experiences. Her one whole-class novel unit of the school year, centered around reading The Outsiders (Hinton), was a unit she had built and taught each year of her career, across multiple states and grade levels. Conversely, Natasha also shared that there were beliefs and practices that had been “coached out” of her while teaching in past schools – things she believed in or cared about that she no longer centered in her teaching. Interest, beliefs, values, and experiences shaped the curriculum in Natasha’s classroom daily.

Differences in Instruction are Rooted in Teacher Beliefs

As each of these brief descriptions illustrates, educators’ understandings of and beliefs about teaching ELA directly shape the education they provide to students. Erin, still closer to her own undergraduate English major, had more of the vestiges of traditional literary study in her classroom. Natasha had rejected more of these traditional trappings of English-as-literary-studies, instead building a classroom where literature was present but just one of the myriad forms of communication privileged in teaching and learning. Each educator cited personal interests and beliefs as being important to their instructional decision-making, underscoring the argument that ELA teachers often have notable autonomy in shaping teaching and learning in their classrooms.

Finding 2: Academic Standards Shape Educator Understandings

In interviews, Natasha and Erin each described professional development that WMS had provided the previous summer as being important to their instructional planning for the 2022-2023 school year. In this professional learning, they explained how they were told to instructional plan with the new (2020) Minnesota ELA standards in mind and, specifically, to select four “priority standards” to focus teaching and learning on for the year out of the 72 ELA benchmarks in each of their grade levels. Selecting priority standards helped to focus both educators’ instruction. As Erin, explained in our initial interview, this kept her from being overwhelmed by the “million” very “jargony” standards, instead letting her “just focus on the skill or the content… of [students’] learning.” Natasha also expressed appreciation for the ways that this approach to planning helped to focus her thinking and planning for the school year.

Because of this school guidance, the 2020 Minnesota Academic Standards for ELA ended up playing a significant role in each participant’s classroom. Each educator readily explained the standards that they’d prioritized and why. For example, veteran teacher Natasha selected standards on the basis of their being being “broad” enough to encompass the work she wanted to do, as well as being aligned to her self-professed beliefs about the work of ELA.

Notably, both participants explained that they selected four standards as their priority standards: two standards from the Reading strand, one standard from the Writing strand, and one standard from the Listening, Speaking, Viewing, and Evaluating Information (LSVEI) strand. This curation of priority standards points to the way that even the organizational structure of the 2020 Minnesota ELA standards may shape teachers’ beliefs about their discipline, leading to a relatively lower priority on teaching literary analysis (discussed much more in Finding 3). If teachers are expected to teach across three distinct strands – Reading, Writing, and LSVEI – it seems unsurprising that this might shape their thinking about how to balance priorities and spend instructional time in their ELA classrooms.

Finding 3: Multidisciplinarity in ELA Impacts the Prominence of Literature

Finally, and closely related to the second finding, the multidisciplinary character of ELA as it exists in U.S. K-12 schools today can be seen to have a direct impact on the time and energy that teachers afforded to teaching literature. As argued earlier in this paper, ELA can be understood to be a multidisciplinary subject; rather than neatly mapping on to one correlating higher education discipline, ELA can be understood to incorporate elements of literary analysis, non-fiction reading, diverse forms of composition, drama, and communications (Rainey et al.; Smagorinsky). As a result, much of the existing disciplinary literacy research centers on literary experts’ literacy practices efforts to translate these practices into ELA teaching at the middle and high school levels. Seen from the perspective of this study’s participating middle school ELA teachers, though, these top-down perspectives on disciplinary literacy seem potentially misaligned to educators’ goals and priorities for teaching. Moreover, this multidisciplinary nature is written into the structure of the new Minnesota State Standards for ELA, with instructors explicitly called upon to navigate these different disciplinary pulls across the enumerated domains for ELA.

Educators who participated in this study were actively wrestling with questions about the role of literary study in their classrooms – rather than being the assumed focus of instruction in their classrooms, these teachers were questioning and potentially decentering literary study in their classrooms. Across the full school year, each only taught a single whole-class novel-length text, and each undertook multiple units of study focused on other literacies – non-fiction reading, rhetoric and argumentation, and diverse forms of composition all played prominent roles in their classrooms. Because of these tensions and diverse pulls, it may be helpful to borrow the framing offered by disciplinary literacy scholars in another field – Bernard and collaborators suggest thinking about disciplinarity in terms of the roles we ask students to take on, the texts that are the focus of their attention, and the disciplinary practices they engage in (Bernard). I’ll briefly consider my observations in each classroom in light of this framework before drawing conclusions about the role of literary study in each classroom.

In first-year teacher Erin’s classroom, the central texts across the school year were diverse; in the unit I observed, study of Maus was the anchor for all study, but students were undertaking extensive informational study and analysis to complete their main end of unit projects. In terms of roles, then, Erin’s instruction pushed students to complete both comprehension- and analytic-focused reading of texts; in her final interview, Erin noted that the types of questions she asked students about Maus shifted over time, as she realized that literal comprehension of events wasn’t as strong as she had expected at the start of the unit, so she added in activities like building a family tree of characters and constructing timelines of events together to encourage literal comprehension of the text, based on student feedback and formative assessments. Analytic roles students took on were (supported) analysis of literary symbols, independent analysis and arguments based on their independent reading of non-fiction texts, and building an argument about historical events they believe should be taught in their school. Finally, in terms of disciplinary practices, Erin’s classes did compose a literary analysis essay as part of their summative assessment of this unit; this more traditional literary study summative was complimented by a text-based argumentative project, focused on their non-fiction reading about another historical instance of injustice and why this instance would be important for future 8th graders to study. Based on these observations about texts, roles, and disciplinary practices, Erin’s instructional design can be viewed as that of a disciplinary pluralist: she still sees a role for literary study in her ELA classroom, and she maintained a balance between literary and informational texts and analysis in her classroom.

Veteran teacher Natasha’s instruction was not built around literary study during my observations: her literature-focused unit for the school year was complete before the start of my study. In terms of texts,then, Natasha focused on informational texts, specifically texts that could push her students to explore argumentation and rhetoric. Students engaged with texts such as famous speeches and short, often educator-created short persuasive texts during this unit; literary reading was expected to be completed outside of school for students’ historical fiction book projects, and this reading was not a focus of class time or energies. With regard to roles, Natasha pushed students to take on analytic roles before applying their insights about rhetoric to craft and present their own arguments – evident in their end of semester debates. Finally, with regard to disciplinary practices, Natasha’s students undertook argumentation and debate in ways more typically aligned to communications skills than to literary reading and analysis. These instructional decisions can be seen as manifestations of Natasha’s questioning about the purposes of ELA teaching and learning. At the end of our initial interview, Natasha described a recent conversation with a colleague who raised the question, “Is it really our job to just produce little English professors?”. Natasha passionately responded that she rejected this view of her work, instead viewing ELA as a multidisciplinary and eclectic field and rejecting traditional whole-class literary study conceptions of ELA.

Although my data is limited—I learned from just two instructors, and only for a span of several months—the ways in which teachers’ beliefs about their work as ELA teachers diverged from the literary-centered orientation of ELA-focused disciplinary literacy research seemed noteworthy. Teachers’ instructional decisions reflected diverse commitments with regard to text genres, the roles they took on in responding to texts, and the discourses they engaged in to demonstrate their learnings. Finally, the relatively pluralist approaches each arrived at in teaching ELA also reflects the balance of the Minnesota Academic Standards for ELA – a balance of informational reading, diverse forms of writing, and listening and speaking skills – suggests that the architecture of these state standards may either reflect or, potentially, shape teachers’ thinking about their roles.

Recommendations for In-Service Educators

On the basis of these findings, several suggestions focused on English Language Arts teachers seem prudent. First and foremost: English Language Arts is a complex, multidisciplinary subject area. As participant Erin noted, we can often “assume” that everyone is on the same page about what ELA is and should do, but when we dig deeper and engage in conversation, we find tensions and conflicting perspectives even among collaborating educators. A critical first step, then, is taking the time to engage in these critical conversations. Utilizing structures like department meetings, professional development, and informal conversations, I encourage teachers to wrestle with the big questions about the work of ELA teachers. What role do we see foundational reading playing in our secondary ELA teaching? This question is especially critical today, amid discussions about the READ Act and its implications for upper-grades teachers. What disciplines and discourses are unique to ELA? How should we balance those unique discourses, such as literary study and analysis, against skills such as teaching writing, reading informational texts, and the broad communication skills that are critical both in school and beyond? The answers to these questions aren’t settled; ELA teachers answer these questions every day with the choices we make in our individual classrooms. Our answers can only get stronger if we reach them through conversation with colleagues.

Secondly, I encourage all ELA teachers to critically reevaluate the role that literary study plays in our classrooms today. If, like the participants in this study, literature has shifted to more of a supporting role in your classroom, explore why. Literary reading has unique powers to both provide insights into the lived experiences of others and to build our aesthetic appreciation (Storm). Moreover, I argue that literary texts have a unique potential to help us wrestle with ethical questions about the world we live in and the world we hope to build for those who will come after us (Taylor). Amid all of the pushes and pulls on our limited instructional time, I argue that we lose something if we lose the aesthetic and the imagined playing a central role in our ELA classrooms; this doesn’t need to look like any one traditional form of literary study, but we would do well to lean into these distinctive attributes of ELA in K-12 schools.

Finally, my study suggests the need to really equip teachers with robust understandings of academic standards, how they work, and how to use them in our classrooms. Notably, the Minnesota Department of Education (MDE) advises against the sort of priority standards based planning that Westview teachers were coached and required to do in this study (Minnesota Department of Education, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): 2020 Minnesota English Language Arts). In this FAQ document, MDE observes that this sort of teacher-defined standard prioritization can lead to incomplete coverage, and can set students up with inconsistent learning experiences year-to-year. Instead, state guidance suggests that teachers should focus on “integration and bundling” of multiple standards into multiple units, and assessment design (including performance tasks) that can give insight into multiple standards concurrently.

However, instructional planning is complex, old habits die hard, and changing educational practices is especially onerous. Learning new standards takes time, requires space to make meaning, and necessitates trust in educator’s skills. During my thirteen years as a K-12 teacher and instructional coach in Missouri, I worked with four different sets of ELA standards, and the support I was most often given when standards changed was either a packaged curriculum or a crosswalk document that would help me plug new standards codes in to my lesson plans and keep teaching the same old things. Neither of these options provides the robust professional learning that teachers deserve when they’re asked to work toward new standards. Teachers are professionals and, with time, support, and space, they’re capable of so much more. Leaning into the robust standards implementation supports being provided by the Minnesota Department of Education, working with colleagues, and giving teachers the space to make meaning of standards will be critically important as Minnesota prepares for full implementation of these standards in 2025-2026.

Conclusion

ELA teachers in Minnesota are currently reimagining what instruction in their classrooms looks, sounds, and feels like amid winds of change: new Minnesota Academic Standards for ELA, the rise of generative AI, increasing book challenges and bans, and increased scrutiny on academic results in reading and literacy post-pandemic. My study has shown that teachers are actively doing this reimagining, based on their own beliefs about ELA, the ways in which context (including the Minnesota Academic Standards for ELA) impacts teaching and learning, and the complexities of navigating a multidisciplinary subject. Increased time to explore the standards, to build or adapt meaningful instructional plans, and to interrogate the purposes of ELA teaching and learning are all essential to address the complexity of ELA teaching in Minnesota’s K-12 schools today.

Works Cited

Bernard, Cara Faith. “Disciplinary Literacy as Curricular and Instructional Practice in Music Teacher Education.” Journal of Music Teacher Education, Sept. 2024, p. 10570837241279021, https://doi.org/10.1177/10570837241279021.

Bloom, Molly. Smash Boom Best. https://www.smashboom.org/. Accessed 3 Apr. 2024.

Fang, Zhihui, and Suzanne Chapman. “Disciplinary Literacy in Mathematics: One Mathematician’s Reading Practices.” The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, vol. 59, Sept. 2020, p. 100799, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmathb.2020.100799.

Goldstein, Dana. “American Children’s Reading Skills Reach New Lows.” The New York Times, Online, 29 Jan. 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/29/us/reading-skills-naep.html.

Hinchman, Kathleen A., and David G. O’Brien. “Disciplinary Literacy: From Infusion to Hybridity.” Journal of Literacy Research, vol. 51, no. 4, Dec. 2019, pp. 525–36, https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X19876986.

Hinton, Susan E. The Outsiders. Viking Books for Young Readers, 1967.

Horowitch, Rose. “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books.” The Atlantic, 1 Oct. 2024. The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/11/the-elite-college-students-who-cant-read-books/679945/.

Kaufman, Julia, et al. How Instructional Materials Are Used and Supported in U.S. K-12 Classrooms: Findings from the 2019 American Instructional Resources Survey. Research Report, RAND Corporation, 2020, https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA134-1.

Legislation. https://education.mn.gov/MDE/about/rule/leg/prod081782. Accessed 29 Jan. 2025.

Luke, Allan. “The Trouble with English.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 39, no. 1, Aug. 2004, pp. 85–95. Zotero, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40171653.

Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. 2nd ed, Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1998.

Minnesota Department of Education. 2020 Minnesota English Language Arts (ELA) Standards Implementation Timeline. Minnesota Department of Education, May 2021.

—. 2020 Minnesota K-12 Academic Standards in English Language Arts. Minnesota Department of Education, 2023.

—. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ): 2020 Minnesota English Language Arts. Minnesota Department of Education, Oct. 2021.

Moje, Elizabeth Birr. “Developing Socially Just Subject-Matter Instruction: A Review of the Literature on Disciplinary Literacy Teaching.” Review of Research in Education, vol. 31, no. 1, Mar. 2007, pp. 1–44, https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X07300046001.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, and Council of Chief State School Officers. Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010, http://www.corestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/ELA_Standards1.pdf.

Patton, Michael Quinn. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Fourth edition, SAGE Publications, Inc, 2015.

Pauketat, Regena, et al. Teachers’ Perceptions of Coherence in K-12 English Language Arts and Mathematics Instructional Systems. Research Report, RAND Corporation, 2023.

Rainey, Emily C. “Disciplinary Literacy in English Language Arts: Exploring the Social and Problem-Based Nature of Literary Reading and Reasoning.” Reading Research Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 1, 2017, pp. 53–71. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.154.

—. “Teaching and Learning Literary Literacy.” Disciplinary Literacies: Unpacking Research, Theory, and Practice, The Guilford Press, 2024, pp. 19–35.

—. What Does It Mean to Read Literary Works? The Literacy Practices, Epistemologies, and Instructional Approaches of Literary Scholars and High School English Language Arts Teachers. 2015. University of Michigan, Doctoral dissertation. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Reynolds, Todd, and Leslie S. Rush. “Experts and Novices Reading Literature: An Analysis of Disciplinary Literacy in English Language Arts.” Literacy Research and Instruction, vol. 56, no. 3, 2017, pp. 199–216.

Ruppar, Andrea L., et al. “Influences on Teachers’ Decisions about Literacy for Secondary Students with Severe Disabilities.” Exceptional Children, vol. 81, no. 2, Jan. 2015, pp. 209–26, https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402914551739.

Saldaña, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 4th ed., SAGE Publishing, 2021.

Shanahan, Timothy, and Cynthia Shanahan. “Teaching Disciplinary Literacy to Adolescents: Rethinking Content-Area Literacy.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 78, no. 1, Apr. 2008, pp. 40–59, https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.1.v62444321p602101.

Siuty, Molly Baustien, et al. “Unraveling the Role of Curriculum in Teacher Decision Making.” Teacher Education and Special Education, vol. 41, no. 1, Feb. 2018, pp. 39–57, https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406416683230.

Smagorinsky, Peter, et al. “Acquiescence, Accommodation, and Resistance in Learning to Teach within a Prescribed Curriculum.” English Education, vol. 3, no. 3, Apr. 2002, p. 28.

—. “Disciplinary Literacy in English Language Arts.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, vol. 59, no. 2, Sept. 2015, pp. 141–46, https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.464.

Sold a Story. Directed by Emily Hanford, American Public Media, 2022, https://features.apmreports.org/sold-a-story/.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. Pantheon Books, 1986.

Stake, Robert E. The Art of Case Study Research. SAGE Publications, 1995.

Storm, Scott. Aesthetic Literacies: A Multi-Method Study of Youth Textual Interpretation and Social Justice in a Digital Learning Ecology. 2023. New York University, Doctoral dissertation. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Taylor, Anna McNulty. Disciplinary Literacy, Reading, and Middle School ELA Teachers: A Multi-Case Exploratory Study. 2024. University of Minnesota, Ph.D. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/pqdtglobal/docview/3072225171/abstract/1F3957C7B41F4C87PQ/9.

Troyer, Margaret. “Teachers’ Adaptations to and Orientations towards an Adolescent Literacy Curriculum.” Journal of Curriculum Studies, vol. 51, no. 2, Mar. 2019, pp. 202–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2017.1407458.

Williams, Raymond. The Long Revolution. Columbia University Press, 1961.

Wineburg, Samuel S. “Historical Problem Solving: A Study of the Cognitive Processes Used in the Evaluation of Documentary and Pictorial Evidence.” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 83, no. 1, 1991, pp. 73–87. Zotero, https://doi-org.ezp2.lib.umn.edu/10.1037/0022-0663.83.1.73.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th Edition, SAGE, 2018.

Learn more about the author on our 2025 Contributors page.