Introduction

Over the last seven years, working in two Midwest teacher education programs, I have become concerned with how many preservice teachers (PTs) see “curriculum” as tangible items, not a process. For many PTs, curriculum is exclusively state or federal standards or a textbook they are required to follow; so, my challenge as a teacher educator is to ensure PTs understand that while “text, materials, lessons, tests, and classrooms are important[,] they are simply not the substance of curriculum or purpose of education” (Slattery 66). I want future educators to see curriculum as a process in which to engage, not barriers that place arbitrary limits on their teaching.

In my teacher preparation courses, arts-based activities, such as writing poetry, are used to encourage PTs to provoke, explore, and challenge students/themselves to learn in varied ways. As a former high school Communication Arts and Literature teacher, I believe deep exploration of language—the beauty of words—provides opportunity to push PTs to step outside their proverbial comfort zone, reinforced by years of standardized tests. It is in this uncomfortable space that I believe preservice teachers grow the most.

I push PTs to realize Pinar’s reconceptualization of curriculum—currere, “the Latin infinitive form of curriculum meaning to run the course, or, in the gerund form, the running of the course” (Pinar 44). I ask these future educators to move from “course objectives to complicated conversations” (47). This change in perspective confounds PTs, as many teacher education programs continue to reinforce the belief that “curriculum is a tangible object – the lesson plans we implement, or the course guides we follow – rather than the process of running the racecourse” (Slattery 66). With this racecourse in mind, I ask students to write poetry, knowing the process is more important than the product.

Therefore, in this article, which I co-author with six of my undergraduate students, I question 1) the implications of PTs’ attitudes regarding curriculum as they begin their teaching careers; 2) how teacher educators provide opportunity for PTs to conceptualize curriculum as more than course objectives; and 3) how poetry provides space for exploring concepts within and beyond the English/language arts classroom. As my six co-authors will soon be in-service teachers in Minnesota, understanding their perspective(s) of curriculum as well as how they see using poetry across different content areas provides a glimpse into the importance of how poetry is/can be taught in K-12 Minnesota classrooms.

Literature Review

Sleeter and Carmona argue, “Curriculum, and who gets to define it, is political because knowledge in a multicultural democracy cannot be divorced from larger social struggles” (3). Political voices in education, struggling for control of schooling, do not always understand that “learning to teach is a complex process” (Reinhardt 288). Some understand “curriculum is not just a script or a blueprint” (Seiki 12), and others expect “teachers are to act as robots rather than professionals when the scripts and the expectations of the teacher and consequently students are shaped by someone else” (Milner 168). Consequently, teacher educators must navigate PTs through these varied perspectives, so they may decide who controls knowledge and skill development disseminated in their future classroom.

Therefore, if my role as a teacher educator is to guide PTs’ self-reflections of their own K-12 experiences, while also pushing them to think beyond their own schooling and to see curriculum as currere, it is imperative to provide PTs room for pedagogical exploration. Amorino offers, “The arts have unique potential as vehicles that can open new ways of thinking for teachers and for students” (190); hence, PTs in my classroom are always offered arts-based options. Burge et al. define arts-based research as taking inspiration from activities and lessons infused with creative arts, such as “poems, film, photography, music-making, storytelling, drama, dance, painting and collage” (730).

In truth, I highly encourage PTs to take advantage of artistic means of expression, for PTs need to be familiar with how they can “use these strategies to meet the student and curricular needs in the classroom” (Lee and Cawthon 8). When asking PTs to evaluate where knowledge comes from in their own experiences and beyond, I encourage pedagogical practices with which they may be less familiar, since “art making creates a new dimension in which to view and understand knowledge” (Degarrod 405). Thus, students in my classroom are often given multiple avenues to express themselves artistically to engage, prod, and discover a multitude of ways to overcome hurdles as they learn to become teachers.

Poetry as Inquiry

Poetry conveys emotion (Baker 4; Leggo 440; Stapleton 449), and as a reflexive tool “provides a window into the heart and soul of human experience” (Smith 877). Poetic inquiry is an umbrella term (Prendergast xx) that uses poetry as the method by which to demonstrate collected and/or self-reflective data from a researcher, which delves into “emotions, feelings, and lives and integrates original poetry into academic research” (Wu 285).

Moreover, poetic inquiry, “a tool for thinking creatively with data” (Grimmett 43), is used across numerous fields of study. Prendergast expounds, “There are examples of poetic inquiry to be found in many areas of the social sciences: psychology, sociology, anthropology, nursing, social work, geography, women’s/feminist studies and education are all fields that have published poetic representations of data” (xxii). In much of this research, poetic inquiry offers “an opportunity to address intimate, affective, and subjective understandings of the world” (Paiva 1), which is especially important with the stressors facing education in a post/pandemic reality (Baker; Faulkner, “Buttered Nostalgia”; Lahman et al.) Additionally, poetic inquiry is evident in varied avenues of educational research, including health professions (Brown et al.), action research (Stapleton), literacy tutoring (Richards), higher education (Persky), and teacher preparation (Wiebe and Yallop).

When using poetic inquiry to frame coursework, PTs can write poetic responses to a plethora of topics in teacher preparation courses as well as across their content courses, for poetry offers a space to explore the inter/intrapersonal emotions associated with teacher preparation.

Thus, as poetry uniquely “unlocks a space of knowing and not knowing” (Brown 7), the act of poetry writing from either personal, self-reflective practices or as a response to readings/discussions in class allows PTs to explore their spirits, hearts, imagination, emotions, bodies, and minds (Leggo 446) often lacking in U.S. public education. Here in these poetic lines, PTs can explore their past K-12 experiences, navigating their own stories of educational defeats and victories, while also exploring their hopes for their future (Görlich 2). Poetry allows for coursework to “evoke emotional responses in readers and listeners in an effort to produce some shared experience between researcher, audience, and participant” (Faulkner, Poetic Inquiry 104). Thus, this article focuses upon the use of poetry as an expression of self/others’ perspectives of curriculum in a teacher preparation course.

Curriculum Statements

Throughout all my teacher preparation courses at St. Cloud State University, a midsize regional comprehensive institution in Minnesota, I encourage students to explore educational ideas in varied manners: narrative, art, and poetry. I find creative expression essential, as these PTs, with different lived experiences, represent the future of the teacher workforce and need to experience varied forms of expression that arts-based activities allow. Their understandings of the teaching profession, beyond their own content, is a primary goal of mine in this core education course.

Co-authors in this study were all PTs in my fall 2021 secondary curriculum, instruction, and assessment course, which is typically taken a semester or two before student teaching. This course, required for all secondary PTs, allows space to for them to discuss and articulate their own perspectives of what curriculum is/means. This space seems even more pertinent with 2021 legislative actions across the United States which prohibit Critical Race Theory discussions, continue to exclude diverse literature and inclusion of LGBTIQ+ identities, and require teachers to publicly provide their lesson plans before the academic year begins. Here among these external, contentious, and political discussions, I ask students to engage in dialogue around curriculum.

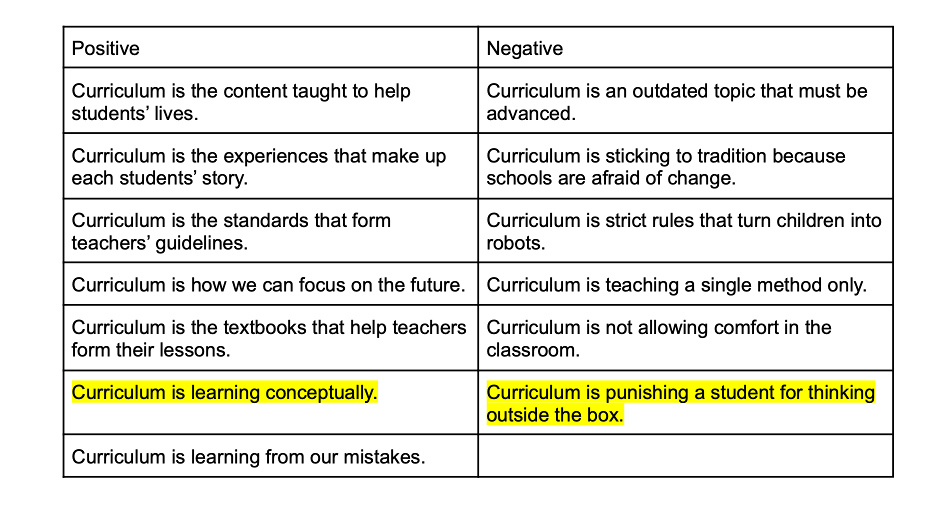

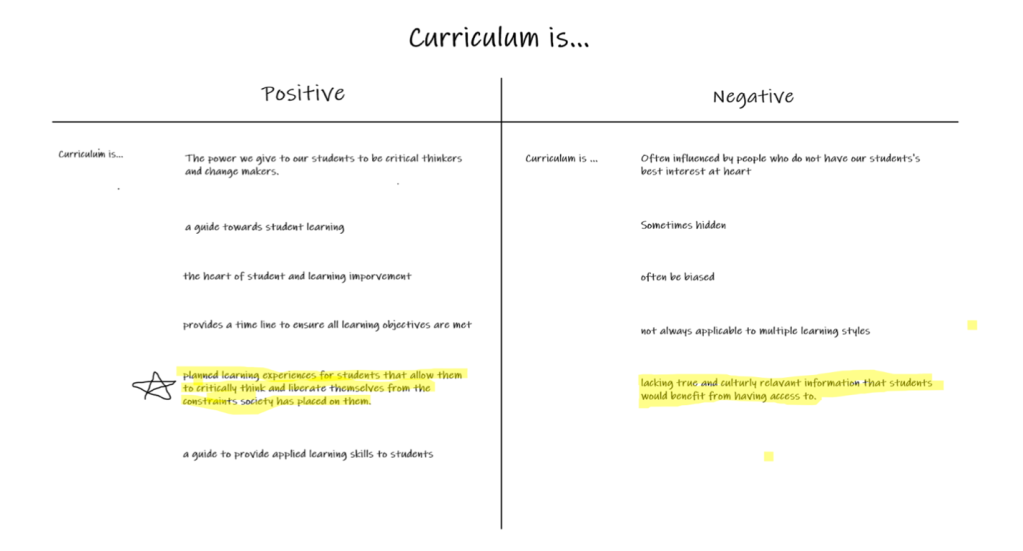

At the beginning of the course, I introduce curriculum as currere to PTs, where I ask them to write curriculum statements to frame our discussions. Individually, PTs create a list of “curriculum statements”—5-7 positive, 5-7 negative—to encourage different viewpoints. Each statement consists of the phrase, “Curriculum is…,” followed by their own opinion statement or their perceptions of curriculum in their teacher education program thus far (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Daniel’s curriculum statement T-chart.

Figure 2. Brittany’s curriculum statement T-chart.

After students create their own lists, I ask them to choose their favorite/most impactful positive and negative statements. Then, students choose the one statement with which they feel most connected. Finally, PTs are given their assignment: choose to either 1) write a 2-page response to your curriculum statement; 2) write a creative, poetic response to your curriculum statement; or 3) create a visual representation of your curriculum statement. This assignment purposefully allows PTs options in how to best express themselves; however, as most of these PTs do not see themselves as artists or poets, I typically do not require students to share their work with others. Nevertheless, offering space to share is important in the artmaking process, so I do encourage PTs throughout the semester to present their creative endeavors with their peers when time and opportunity allows.

The following narratives, constructed from original poetry submissions and email correspondence regarding the process, explore six of the poetic responses to this assignment in the students’ own words.

Lidiah: Projecting Our Existence

Poetry is a passion of mine. I feel really at home when I write. It is the most meaningful and fruitful avenue I have found to express myself so far, so when asked to write for class, I was thrilled for the opportunity to combine my passions and let them feed off each other. There is something powerful about writing with a particular purpose about a moment that might have originally seemed so finite and negligible and exploring to see what might have grown from that.

When I was five,

I heard my name read aloud

in the library of my elementary school

as a character in a story book

for the first time.

I was a tiny green frog.

I remember the magic of seeing myself

Someplace I didn’t expect,

and I’ve spent the rest of my years

finding and searching for my reflection in things that feel like me.

Books,

Movies,

Art,

Poetry,

My brother’s smile,

My cheeks, tear-stained, and hot under a spotlight, center-stage.

I’ve seen myself in texts and novels

That felt like they were written and chosen

For me.

And in turn,

I’ve learned,

learned so much,

and by that,

built a life

that screams my name aloud to the world…

I know not everyone is so fortunate,

to see themselves reflected and respected

in a curriculum curated

for their growth,

for their flourishing,

for futures that project their existence

into the rest of the world.

I know there are beautiful, untended minds

that never read a poem that felt

like it was written for their ears.

Friends,

Who never read their histories—

their true histories—

under the watchful eye of someone

who could help them make sense of it.

And I wonder who their curriculum was written for?

—and why it wasn’t written for them?

and now I’m promising myself

and every child

every beautiful, untended flower

that I will water them in their own reflections

until the sunlight that gleams off their green stems and leaves

beams rainbows into the sky for everyone to see.

And read their names aloud, like someone did for me.

Writing this poem, I felt a well of purpose and direction. I use poetry as a journaling technique in my daily life. I find it difficult to write actual journalistic summaries of my life, and I prefer to try and artfully articulate my feelings and experiences. This poem was, at first, difficult to start. I had chosen my “prompt” which was “Curriculum is centered around the best interest of the student.” And while I feel that strongly, it was difficult to pinpoint just when and how I remember that in my own educational experience.

Fortunately, I was able to call upon a very vivid memory from either preschool or kindergarten, I can’t be sure. We were sitting in the school library, and our teacher was reading aloud a picture book to us. I rarely met other kids with the same name as mine, heard songs with my name in them, or watched movies with characters that shared my name, so to hear it and see my classmates’ heads turn and look at me was a moment that has stuck with me.

Once I had written the line “finding and searching for my reflection in things that feel like me,” it was so easy and natural and exciting to write the rest of the poem. I think I wrote the entire thing in about fifteen minutes. It felt like the poem was flowing out of me, like a stream of unbridled energy.

Bee: Able to Reflect Different Cultures

I plan to teach art in middle or high school, and I will likely be teaching somewhere in Minnesota. When I was asked to write poetry as an assignment in the curriculum course, I was initially skeptical. Normally I expect assignments, especially at the college-level, to be something along the lines of writing a paper or answering questions on a worksheet. I am not used to having an assignment be based on any kind of artform outside of my art courses, so it was a welcome change from the kind of work I usually do in education classes.

let’s go on an adventure

we’re going across the world

to where its new, to where its familiar

in search of knowledge

we’re meeting new people

we’re meeting people who look like me

and who look like my friends

we’re meeting men who live happily with their husbands

and women who want to spend forever with their wives

what do these people believe in?

what do they find important?

how delightful to find

they’re just like me

what do they have to say?

what do they want everyone to know about them?

the book closes

the video ends

the speaker finishes their speech

how good to know

we’ll soon go on an adventure

once more

when we return to class.

The process I took to write my poem was quite simple. I thought about the subject from a few different perspectives. For example, I thought about the ability of curriculum to reflect different cultures from the perspective of the teacher. How would this look from the view of someone using that curriculum? When I attempted to brainstorm lines for a poem from this perspective, I did not get the kind of mood I wanted to emphasize. After that, I moved on to the point of view of the student. Specifically, I wanted to embody the perspective of a younger student. The reason I did this was because younger students have much more of an openness and expressiveness when it comes to learning. I felt that that lends itself to more of an expressive and excited mood, which is what I wanted this poem to have. After that, it was quite easy to come up with a poem that felt more authentic to what I wanted to say.

Daniel: Punishing Students for Thinking Outside the Box

When asked to write poetry, and really, when asked to create any kind of art, I didn’t really understand how it had to relate to teaching of mathematics at all. I didn’t think there would be any connection to my content area. I couldn’t have been more wrong. I knew it from the beginning; I just didn’t know I knew it. Mathematics, in a way, is learning to be creative—learning to find unique solutions to problems. A huge part of my teaching philosophy is letting students find the ways to solve problems that work for them. It doesn’t matter if it is the way I taught. It just matters that those students are comfortable with their method, and that they know it will work for all situations.

Sarah was excited to go to school today.

When doing last night’s homework,

She found her own method that helped her understand

A concept she’s been struggling with.

She was excited to tell her teacher all about her method,

And that by using this method

She will be able to finish the homework so much faster than before.

But Sarah’s expectations did not match her reality.

When the teacher saw Sarah’s work, she asked her,

“What do you think you are doing?”

“Sarah…” the teacher said.

“This is not what you were taught. Take this back home

And bring it back once you do it correctly.”

Sarah’s excitement drifted away rapidly.

She thought her teacher would be proud.

Happy.

Encouraging.

The exact opposite was true.

For the rest of the day, Sarah was dejected.

“What if my other teachers are like this?”

She thinks to herself. Sarah may never enjoy school again.

At home, Sarah tries doing the work how she is supposed to do it.

According to her teacher,

Sarah did her homework the right way.

But what did she learn from it?

She learned to listen to her teacher.

She learned that only one method works.

She learned to think like everyone else.

She learned to not think outside the box.

Through experiences with peers and high school and middle school students, both online and in person, I’ve learned that some teachers dislike when students do things a different way. Why, though? If the method works, then there shouldn’t be a problem. It bothers me that some teachers won’t accept alternate solutions. It is as if they are rejecting creativity, forcing students to think like one another. Building them like robots. I wanted to express this situation in my poem, and I figured the best way would be to put the reader in the eyes of the student.

Tyler: Curriculum Is Political

As a future health educator, curriculum is extremely important, especially when it comes to sex education and contraceptives. I want people to know that the lack of education is not adequate to prevent teen pregnancy and promote safe sex. I think there is a big difference between teaching sex education and promoting students to be sexually active. I think that my job as a health educator is to provide students with the information and tools to live healthy and fulfilling lives. Some school boards still insist that we should continue to teach abstinence only, which only harms our students and their future. This poem is a story about a young girl and boy who fell in love but never received proper sex education, and now are experiencing teen pregnancy.

Sarah sobs in the bathroom before first period.

Sarah feels like she has no one to reach out to.

Sarah asks herself, “How did this happen?”

Sarah’s life will never be the same.

Sarah was just an ordinary girl.

She enjoyed pep rallies and getting ice cream with her friends.

She had one younger sister and two loving parents.

Sarah’s life will never be the same.

Sarah has a boyfriend named Jon.

Jon is a senior and captain of the football team.

Jon and Sarah were young and in love.

Jon’s life will never be the same.

One mistake will last a lifetime.

Some may see it as a blessing.

Some may see it as a curse.

Everyone knows it will not be easy.

Sarah is a mother to be.

Jon has yet to know.

My initial thoughts for writing poetry were very hesitant. I haven’t written poetry since middle school, and even then, I felt uncomfortable writing poetry and being vulnerable in my writing. However, I feel that there is an element to poetry that reaches emotions that other forms of writing do not, and the objectivity of poetry is beautiful because it allows people to make their own conclusions after reading.

Mallory: Predetermined Value

I plan to teach secondary language arts in Minnesota following graduation. I have always enjoyed writing poetry, so I was excited for the opportunity to write a poem for an assignment. It is an unconventional ask for an upper-level college class about curriculum, but that played into the excitement of it all. Writing poetry allows me to portray thoughts and ideas otherwise left unsaid.

Our entire lives

Based on test scores

From when we were

7, 10, 13, 16, 18…

Children.

Our entire life trajectory

Determined by second grade.

Because Annie skipped breakfast,

Jacob’s uncle died yesterday,

Noah’s parents finalized their divorce,

Olivia and her family are getting evicted.

A singular day

Changed the trajectory of “success”,

Self-worth,

Perception of themselves as students,

As a learner…

Damaged and shattered.

Curriculum rooted in test scores,

A number on a piece of paper

Deciding between Doctor or Unemployment.

Doors that should have been open

Remain locked and boarded up,

An unreachable dream

For so many bright and determined children.

Their dreams are taken from them

By a single piece of paper.

By a bad day in eighth grade,

By self-doubts

Because school told them they were not good enough.

Education should be liberating,

Thrilling,

Life-changing,

A dream come true,

But it is the bane of many students.

Writing this poem came naturally to me because I was drawing on frustrations I had as a student myself. In high school, I remember feeling pressure to get high marks on every single assignment, quiz, test, etc., because otherwise, I was a failure. I shared this feeling of failure with many of my peers who were bright and extraordinary thinkers, but they did not or could not conform to the unreasonable means of how education measures success.

One of my favorite teachers from high school did not believe in tests, which was a shock to me when I entered her Language Arts classroom in 9th grade. All I had ever learned was to be a “good student” by getting As on tests, but her pedagogy changed that. I grew more in her classroom as a student, writer, and person than I did in any other class. Of course, in other classes, I still struggled with feeling like a failure because mistakes were not accepted, grace was not given, and an “A” was the only form of acceptance. That never sat right with me. I saw many of my peers fall through the cracks because they were not able to attain the “A” on a test, even though they were some of the most incredible thinkers I have ever met. I feel very strongly about how poorly education measures “success,” so writing this poem was like telling myself from high school that numbers will never truly determine your worth, even if that’s what the education system drills into your head.

Brittany: Freedom

After critically thinking about what I believe to be true about curriculum, I looked at my list and realized that so much of what I brainstormed was negative. I concluded that I had such high hopes of what curriculum was supposed to be and that the current reality is sometimes a sellout. After my realization, it was hard to put my feelings into words because I wasn’t at peace with my claim. I didn’t want it to be true. I ended up accepting my anger and letting it escape onto the page. Slowly my anger turned towards a vision and hope. I went back to revise, looked at my style and word choice, played around with some formatting, but mostly I said what I needed to in my first draft.

You’ve been biased and deceitful.

served the elite, that alienates and imprisons who

you were created for

youth

To serve to guide to liberate

When did you hide and how much did they pay you

To sell out to a system that harms and degrades our most vulnerable

Tells them lies of who they are and who they cannot be

But I know you are more.

I see who you could be

I know hope’s at your core

Fostering critical thinking and opening doors

Leading students to greatness

Guiding their teachers to empower

You can break chains and liberate

Stop serving the elite

Instead unite and set free who

You were created for

Youth

To serve to guide to liberate.

This poem is meant to call out the current problems in our education system, but also to point towards the beauty that public education can be. It is meant to be an honest, angry, and hopeful reflection. During primary and middle school, I dreaded poetry month—that is, if we even got around to it that year. I felt so confined in the countless modes of poetry we were taught. In high school, I fell in love with reading poetry. I would buy any poetry book I could find at a secondhand store. I adored when my friends let me read their art, but still, I could never create my own. I felt trapped by expectations and my fear of failure. Eventually I began to write, but threw away or burned every single draft, thought, and masterpiece I let myself create.

Currently, when I sit down to write in my poetry journal (that I now keep and treasure), I still feel that pressure breathing down my neck to make it beautiful. I often wonder whose standard of beauty I aim to achieve in my writing. Am I still writing for my middle school English teacher who told me that ‘crate’ and ‘bake’ didn’t rhyme and that I’d have to try again? In the classroom, I hope to never be a perpetrator of the feelings of confinement that students often feel when asked to write poetry. I want to teach my students that beauty is letting yourself escape to the page. This lesson is the precursor to teaching a single poetic device.

Fostering poets starts with providing poetry for students that doesn’t fit in the acrostic, haiku, limerick, and rhyming boxes we too often teach and learn. Can we please start letting our students in on the secret that free verse poetry is actually poetry? Exposing students to contemporary poetry and spoken word will help show them why poetry matters. Only then can our students appreciate sonnets, villanelles, odes, and concrete poems. Only then can we show them the multitude of poetic devices that enhance writing. Only then will they allow themselves to escape to the page.

Poetry as a Pedagogical Tool

Poetry writing offers a platform for thought-provoking discussions to promote engagement as demonstrated in these six narratives. Tyler’s poem, “Curriculum is Political,” explores the political nature of sex education curriculum. His poem about two teenagers, Sarah and Jon, explores the emotional component of their situation, allowing for complicated conversations surrounding teenage pregnancy, sex education and/or contraceptives, without placing judgement on them. As Tyler correctly points out, politicization still occurs around controversial topics such as these. Furthermore, the political nature of whose voices are and are not heard in curriculum are evident in Lidiah’s poem, where the sole utterance of her name led to connection of text, and a moment that stuck with her for years. Bee, in their poem, addresses the topic of same-sex marriage, another complicated conversation with divisive political opinions, but the inclusion of sexual orientation allows students to make connections with curriculum that could otherwise be silenced. In all three poems, space was provided to explore the emotionality of identity, make personal associations with curriculum, and reach out to often marginalized voices in schools, absent judgement. This is the power of allowing poetry writing in the classroom.

However, not all English/language arts teachers, preservice and in-service, appreciate poetry. When I first heard a colleague tell me they did not like poetry, I was astounded. How could an English teacher not appreciate poetry? Then it hit me. This novice teacher was a product of the same system I encourage my PTs to criticize; she disliked poetry because it, too, had become standardized. Instead of embracing the beauty of words, the exquisite nature of language, this teacher had been taught to view poetry through the eyes of test questions—losing the splendor of emotionality. Thus, I was not surprised that, as I moved into teacher preparation, I would hear numerous PTs express their disdain for poetry and/or poetic writings.

When students tell me they hate poetry or fear teaching it, I ask them to shift their perspective. As Bee explains, “A lot of people have a very rigid idea of what poetry is and what it looks like when written by students, but the truth is that poetry is a really good way to help students express creativity.” Thus, just like curriculum, think of poetry as a process, not a hurdle to overcome. Allow students (and yourself) to write poetry: ignore syllable counts, overlook stanza alignment, forget end rhyme, and disregard figurative speech. Just let students write. As Lahman et al. explain, “The primary way one learns to write poetry is to read, read, read poetry; write, write, write poetry; edit, edit, edit poetry; and share, share, share poetry” (894), not through continued focus on format and limiting arbitrary constraints.

As Tyler reminds us in his narrative, “Poetry reaches emotions that other forms of writing do not.” Thus, when we step away from constantly requiring specific poetic format, figurative speech, and rhyming scheme to evaluate students, as Brittany advocates, we focus on a manner that allows students to grow, learn in creative ways, and as Daniel explains, “find unique solutions to problems.” Through this perspective we see the art of poetry as a place of self-discovery, and once students feel comfortable engaging with/in poetry, learning about poetic devices will naturally follow in an authentic manner.

Outside the Poetry Unit

My PT co-authors represent multiple content areas: English/language arts, mathematics, health, and art; however, each of them found ways to use poetry as a pedagogical tool in their content area (see Figure 3), regardless of their initial hesitation. In my teacher preparation classes, I suggest poetry as an option for PTs to express their feelings about curriculum. In my high school communication arts and literature classroom, I offered students the chance to write a poem for a warm-up, as a response to a short story, to brainstorm ideas, or to articulate prior knowledge while introducing a topic. Whenever I could encourage poetry outside a poetry unit, I did. These options make poetry more accessible to students and provide the freedom to focus on their emotions, not poetic devices. If PTs learn to provide options for poetry outside the English/language arts classroom, then poetry, as a means for self-reflection and discovery, becomes commonplace for students, which encourages poetic expression and leads to a more robust exposure and appreciation of poetry.

| PT | Content Area | Poetry Use |

| Bee | Art | Create artwork based on themes and moods in poetry, blackout poetry |

| Lidiah | Communication Arts/Literature | Co-teach with history classes to write poetry to explore oppression, law, tragedies, etc. |

| Daniel | Mathematics | Write poems involving inequalities. |

| Tyler | Health | Explore topics such as sex education, healthy relationships, eating disorders, etc. |

| Mallory | Communication Arts/Literature | Find a safe space to express oneself; blackout poetry, free verse, unique to their own lives. |

| Brittany | Communication Arts/Literature | Writing prompts, heart maps, writing workshops are all wonderful ways to create a foundation for poetry |

Figure 3. Uses of poetry across content areas.

This cross-curricular understanding of poetry as a mechanism to explore emotionality of a topic and provide a space to thoughtfully engage is important not only in the language arts classroom, where poetry is a state/national standard, but throughout all learning in a school, as poetry is pedagogical tool that transcends grade level and content area.

Discussion

Over the years, through this curriculum statement activity, PTs offer positive statements (“flexible,” “changing,” ‘rewarding”), negative statements (“limiting,” privileged,” “unfit”), and neutral statements (“standardized,” “shared knowledge,” “content based”)—providing me with insight into PTs’ perspectives regarding K-12 curriculum. In the PT poems/narratives above, Lidiah and Bee understand curriculum as a space for exploration of culture and one’s own self, while Daniel and Mallory both see curriculum as either possibly punishing students and/or limiting their creativity, if not constantly checked. Tyler views curriculum in a political context, and Brittany articulates both the pitfalls and potential of curriculum. These varied perspectives are important to consider when regarding curriculum, regardless of the content area. As educators, how do we approach our curriculum: explicit, null, and hidden? As Brittany explains, “What we teach matters. What we choose not to teach matters. What we do not mean to teach matters. Curriculum matters.”

Teaching curriculum as a set of materials to future teachers is vastly different than contextualizing curriculum as a process, enduring ups and downs, obstacles, successes, and continually redefining the goal mark. The latter allows for curriculum to be a living, breathing experience, not the hurdles placed in front of them, as Daniel and Mallory poetically explain.

If “education is meant to draw our own meaning out of ourselves and give us the ability to see that meaning, to see who we are” (Groman 14), then what implications are there for future educators who hold a negative perspective of curriculum? What limits are placed upon teachers, and in turn, their future students, if educators see curriculum as simply a test score? Daniel, Mallory, and Brittany explain their growth in re/understanding curriculum, but do all preservice and in-service teachers come to this same epiphany?

A Shift in Understanding

For my teacher preparation classes, the shift to understanding curriculum as currere comes from allowing PTs the freedom to make mistakes, explore ideas in different methods, and step away from their preconceived ideas of curriculum for a few moments to re/think what their classroom goals are. Mallory explained the impact that the shift from objects (tests, quizzes) to a growth mindset made a huge impact on her in school. This change in perspective allows teachers to facilitate discussions on important concepts and connections—even across content areas—and not emphasize the need to read a predetermined number of pages or complete a multiple-choice quiz within a class period.

I remind PTs, similar to how Sleeter and Carmona explain, “Thoughtful teachers can use a wide variety of resources to help students expand their understanding, ability to think, and ability to communicate ideas” (145). For me, arts-based assignments allow for autonomy of students, imperative for working with “different cultures and the challenges of a pluralistic society” (Lemlech 309), as described in Bee’s poem. As a teacher educator, I embrace my PTs’ prior mis/understanding of curriculum and provide each of them space to move beyond their own K-12 notions of knowledge and help them understand curriculum as an art—a journey, not just a destination.

Dr. Heidi Jones, reading department chair and 7th grade humanities and reading teacher in Robbinsdale Area Schools, reminded me recently that curriculum isn’t just the book you are reading in your class; on the contrary, the book is the tool to help your students understand an idea or theme with wider, worldly implications. This perspective allows for Pinar’s complicated conversations. When using state or national standards, text(s), or a lesson as a jumping off point to engage in important conversations, students grow and make connections. Curriculum is the process that begins the exploration. Teacher preparation programs must continue to turn a critical eye to standardized tests and encourage PTs to poke, prod, and interrogate the expectations to fully understand how they can use materials placed in front of them as a starting point to the race. I assert that if PTs understand curriculum as currere, instead of the obstacles in their way, then curriculum becomes the entire race as well as the wind that pushes them forward, which is key for these novice PTs.

To complicate the discussion of Pinar’s currere further, I ask PTs if everyone is running the same race in education. Emphatically, PTs tell me no, there is no way. Then, why do some in-service and preservice educators continue to perceive curriculum as merely tangible objects: books, standards, guides, quizzes, and exams? If students are all running distinctive races, then we can assume they possess different skills, demonstrate varied abilities, and need different strategies. Therefore, teacher preparation programs must teach, promote, and encourage pedagogical practices that are, as Lidiah explains, “relatable to all students, not just White, cis-gendered, heterosexual young men.” The shift in re/defining curriculum as currere, using pedagogical tools such as poetry to provide space for complicated conversations, must start in teacher preparation programs and continue in schools.

Works Cited

Amorino, Joseph. S. “An Occurrence at Glen Rock: Classroom Educators Learn More About Teaching and Learning from the Arts.” Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 90, no. 3, 2008, pp. 190-195, https://journals-sagepub-com.scsuproxy.mnpals.net/doi/pdf/10.1177/003172170809000307. Accessed 29 December 2021.

Baker, J. Scott. “Poetry and Possible Selves: Crisis Theory with/in Teacher Education Programs.” Teaching and Teacher Education vol. 105, 2021, pp. 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103393. Accessed on 27 October 2021.

Burge, Amy, Godinho, Maria Grade, Knottenbelt, Miesbeth, and Loads, Daphne. “‘… But We Are Academics!’: A Reflection on Using Arts-Based Research Activities with University Colleagues.” Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 21, no.6, 2016, pp. 703-737. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1184139. Accessed 29 December 2021.

Brown, Hilary. “Found Poetry: Reimagining What Is Present and What Is Absent through the Journals of Her Life.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, vol. 20, no.1, 2020, pp. 7-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1532708619884958. Accessed 29 December 2021.

Brown, Megan, E. L., Kelly, Martina, and Finn, Gabrielle M. “Thoughts that Breathe, and Words that Burn: Poetic Inquiry within Health Professions Education.” Perspectives on Medical Education, vol. 10, 2021, pp/ 257-264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-021-00682-9. Accessed 27 October 2021.

Degarrod, Lydia N. “Making the Unfamiliar Personal: Arts-Based Ethnographies as Public-Engaged Ethnographies.” Qualitative Research, vol. 13, no. 4, 2013, pp. 402-413. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468794113483302. Accessed 29 December 2021.

Faulkner, Sandra L. “Buttered Nostalgia: Feeding My Parents During #COVID19.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 1877-1900. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211012478. Accessed 27 October 2021.

Faulkner, Sandra L. Poetic Inquiry: Craft, Method, and Practice, 2nd Ed. Routledge, 2020.

Görlich, Anne. “Getting in Touch: Poetic Inquiry and the Shift from Measuring to Sensing.” Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol. 17, no. 2, 2020, pp. 182-192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1442685 Accessed 18 April 2021.

Groman, Jennifer L. “What Matters: Using Arts-Based Methods to Sculpt Preservice Teachers’ Philosophical Beliefs.” International Journal of Education & the Arts, vol 16, no. 2, 2014, pp. 1-17. Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v16n2/. Accessed 14 December 2016.

Jones, Heidi. Personal Interview. 27 December 2021.

Lahman, Maria K. E., Rodriguez, Katrina. L., Richard, Veronica. M., Geist, Monica R., Schendel, Roland K, and Graglia, Pamela E. “(Re)Forming Research Poetry.” Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 17, no. 9, 2011, pp. 887-896. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800411423219. Accessed 18 July 2018.

Lee, Bridget, and Cawthon, Stephanie. “What Predicts Pre-Service Teacher Use of Arts-Based Pedagogies in the Classroom? An Analysis of the Beliefs, Values, and Attitudes of Pre-Service Teachers.” Journal for Learning through the Arts, vol.11, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-15. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2xg3n0xf. Accessed 14 December 2016.

Leggo, Carl. “The Heart of Pedagogy: On Poetic Knowing and Living.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, vol. 11, no. 5, 2005, pp. 439-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/13450600500238436. Accessed 2 March 2016.

Lemlech, Johanna K. Curriculum and Instructional Methods for the Elementary and Middle School, 7th Ed. Allyn and Bacon, 2020.

Milner, H. Richard. “Scripted and Narrowed Curriculum Reform in Urban Schools.” Urban Education, vol. 48, no. 2, 2013, pp. 163-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0042085913478022. Accessed 10 June 2019.

Paiva, Daniel. “Poetry as a Resonant Method for Multi-Sensory Research.” Emotion, Space and Society, vol 34, 2020, pp. 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100655. Accessed 12 November 2021.

Persky, Julia. “Higher Education and the Ethic of Care: Finding a Way Forward During a Global Pandemic.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, vol, 21, no. 3, 2021, pp. 301-305. https://doi.org/10.1177/15327086211002776. Accessed 27 October 2021.

Pinar, William F. What Is Curriculum Theory?, 2nd Ed. New York, New York: Routledge, 2012.

Prendergast, Monica. “Introduction: The Phenomena of Poetry in Research: ‘Poem Is What?’ Poetic Inquiry in Qualitative Social Science Research.” Poetic Inquiry: Vibrant Voices in the Social Sciences, edited by Monica. Prendergast, Carl Leggo, & Pauline Sameshima, 2009, Sense Publishers, pp. xix-xlii.

Reinhardt, Kimberly S. “Discourse and Power: Implementation of a Funds of Knowledge Curriculum.” Power and Education, vol. 10, no. 3, 2018, pp. 288-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1757743818787530. Accessed 10 June 2019.

Richards, Janet C. “Educing Education Majors’ Reflections about After-School Literacy Tutoring: A Poetic Exploration.” International Journal of Education & the Arts, vol. 17, no. 16, 2016, pp. 1-7. Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v17n16/. Accessed 12 July 2017.

Seiki, Sumer. “Transformative Curriculum Making: A Teacher Educator’s Counterstory.” Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue, vol. 18, no. 1 & 2, 2016, pp. 11-24. EBSCOhost, search-ebscohost-com.scsuproxy.mnpals.net/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=118439814&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed 10 June 2019.

Slattery, Patrick. Curriculum Development in the Postmodern Era: Teaching and Learning in an Age of Accountability, 3rd Ed. Routledge, 2013.

Sleeter, Christine E., & Carmona, Judith Flores. Un-Standardizing Curriculum: Multicultural Teaching in the Standards-Based Classroom. Teachers College Press, 2017.

Smith, Elyssa B. “Poetry as Reflexivity: (Post) Reflexive Poetic Composition.” Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 26, no. 7, 2020, pp. 875-877. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800419879202. Accessed 27 October 2021.

Stapleton, Sarah R. “Data Analysis in Participatory Action Research: Using Poetic Inquiry to Describe Urban Teacher Marginalization.” Action Research, vol. 19, no. 2, 2021, pp. 449-471. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1476750318811920. Accessed 1 November 2021.

Wiebe, Sean, and Yallop, John. J. Guiney “Ways of Being in Teaching: Conversing Paths to Meaning.” Canadian Journal of Education, vol. 22, no. 1, 2010, pp. 177-198. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/canajeducrevucan.33.1.177. Accessed 1 November 2021.

Wu, Botao. “My Poetic Inquiry.” Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 27, no. 2, 2021. pp. 283-291. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800420912800. Accessed 27 October 2021.

Learn more about the authors on our 2022 Contributors page.